In recent times, the UK’s economy, particularly its public finances, has looked a grim state, becoming a ship weighed down by anchors of uncertainty, with Chancellor Rachel Reeves striving to unmoor it and steer toward calmer waters. Truthfully, she has inherited a largely indebted balance sheet, derived from Britain’s stagnant economic growth, along with costly government measures to address Covid-19 and surging energy prices. This drifted astray her initial fiscal plans of greater investment in public services, green initiatives, and fiscal prudence. But as we approach the new tax year, updated fiscal measures have been proposed and will soon be implemented upon April 6th, but what will be the impact of this?

Last Wednesday (26th March), Reeves delivered her Spring Statement, introducing a £14bn repair package in a bid to resolve the UK’s fiscal deficiencies. Notably, welfare expenditure has been cut, saving £3.4bn by 2029-30, as highlighted in a recent FT article by Romei and Hughes. Although this pushes 250,000 people into relative poverty – where the poverty threshold is set at 60% of the national median income and compared to households’ disposable income, as defined in a 2011 study by Notten & De Neubourg. Other reforms such as cuts in day-to-day departmental spending, overseas aid and tax compliance measures are also being implemented to reduce the UK’s fiscal shortfall.

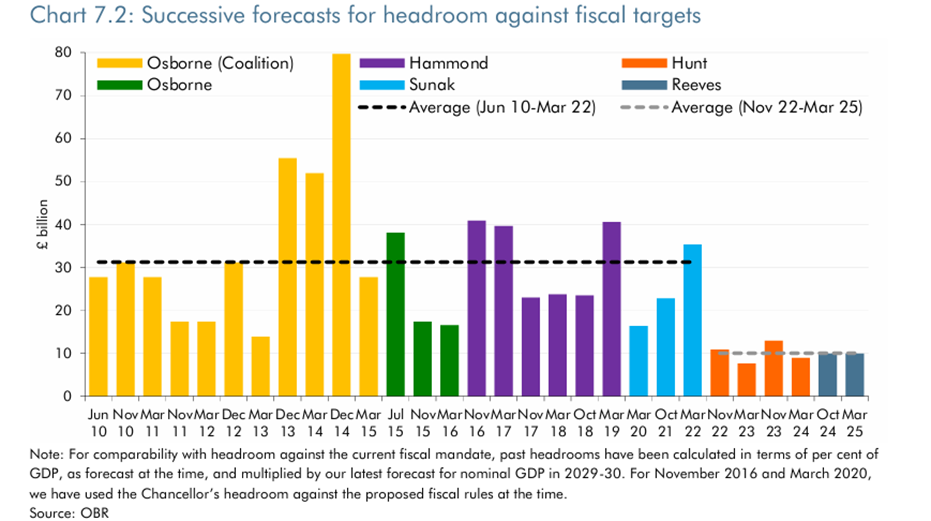

The Chancellor’s ‘Fiscal Headroom’ – the difference between what she’s planning on raising in taxes and what she’s planning on spending or borrowing – is forecasted to be £9.9bn in 2029-30, according to Sproule & Mahoney in their Handelsbanken podcast in March. This is a precarious figure which had effectively been wiped out recently by the combination of lower tax revenues, high debt servicing costs (Sproule & Mahoney, 2025) and global trade tensions. While much to the concern of analysts, Reeves has set aside this figure to ensure compliance with her fiscal rule (balancing current spending with tax receipts by 2029-30), but the FT reports the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has warned that this headroom is highly vulnerable to extinction due to external shocks – particularly a trade war.

(OBR, 2025)

Reeves’ fiscal headroom is shockingly low compared to historical fiscal mandates; approximately one-third of the average headroom Chancellors had set aside pre-2022, illustrated in the chart above, sourced from the OBR’s March 2025 fiscal outlook report.

Last October, UK economic growth was forecasted at 2% for 2025, which the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has since slashed by half to 1%. This has all posed the question as to whether we expect to see tax rises soon, a prospect Reeves has declined to speculate on, according to Parker and colleagues in the FT. From a government revenue perspective, a significant portion of their fiscal dividend derives from tax receipts – taxing sales (VAT), corporate profits, salaries (income tax) etc. Assuming growth is slower, these revenues will fall, generating less capital for the government to spend on the budget. Furthermore, with taxes as a share of GDP projected to rise to 37.7% by 2027-28, this significant fall in forecasted economic growth could severely undermine the sustainability of this headroom.

In addition to these concerns, the government’s decision to increase National Insurance contributions (NICs) adds another layer of complexity to the economic outlook. The rise in NI, by 1.2 percentage points to 15% from April 6th, intends to generate £25bn a year in revenue, as highlighted in a BBC News report by Mark Race, but places an increased financial burden on both workers and businesses. Employers face elevated payroll expenses, whilst employees see direct cuts in their disposable income, exacerbating cost-of-living pressures. This additional tax burden could temper momentum and present Reeves an increasingly difficult balancing act – one that may force her hand towards further tax hikes if economic growth underperforms.

Gilt Market Shake-Ups

In these circumstances, if Reeves still remains committed to avoiding tax increases, the government will have minimal leverage for budget expenditures, effectively tying income projections to borrowing requirements. The Gilt market has experienced notable movements recently, as their issuance has skewed away from longer-dated securities. This adjustment was underlined by Cheung and Curran on AmplifyME’s Market Maker podcast, who highlighted there is now a clearer understanding of the future supply of government issuance and the shift incorporates borrowing across bonds of varying durations (e.g. 10-year, 7-year, 2-year). This allows the government to spread its debt load and redemption payments, and the trend has shifted towards short-term borrowing because interest rates are expected to come down. Acquiring short-term debt means the government can avoid locking in higher rates on long-term bonds, so when rates eventually drop, they can pivot towards longer-term bonds at a cheaper cost.

Further evidence of the UK’s struggling financial health resides in their rising public debt burden, which far exceeds its international peers. This heightens concerns as the Spring Statement’s spending cuts would provide only a temporary fix to deeper budgetary challenges like rising age-related costs, as described recently in the FT by Fleming, Romei, and Smith. According to the International Monetary Fund’s 2024 outlook, the UK’s gross government debt stood tall at 101.8% of GDP, which can be attributed to the synergy of high interest rates, relatively high proportion of index-linked debt, and slower growth, making servicing additional debt more burdensome than their global counterparts – emphasised by Flemming and colleagues in the FT. As financial demands escalate, particularly in defence spending, the burden on the UK’s public purse grows heavier, constraining opportunities for future investment, and ever-growing debt interest repayments.

Deceptive Inflation Figures

Wednesday (26th March) morning also saw the UK’s February inflation announcement, which at first glance seems promising, but more than meets the eye. Inflation fell to 2.8%, lower than expectations. However, the ONS and Bank of England anticipate this to trend higher at around 3.7% by Autumn this year due to the rising energy cap. Whilst many households are on a fixed deal, Ofgem has warned that the new cap, rising 6.4% from April, will still impact them, given the cascading effect energy prices have on food inflation.

Wage growth has been strong in the last year, on the back of very weak growth twelve months prior, and the UK household savings ratio reached 12% in Q4 2024, its highest-ever savings rate outside of the freak Covid pandemic, according to recent ONS data. In fact, since COVID, for every single quarter in the last 5 years, the UK’s household savings rate has been higher than the US, and their consumer spending divergence has been growing, hence acting as a powerful catalyst for the disparity in their economic performance. This was stressed by Cheung and Curran, who noted that in the US, cash being spent is 15% higher than pre-covid, compared to the UK’s drowsy 2% rise.

However, with the inevitable rise in utility costs and hence reduced disposable income for the average UK consumer, questions arise as to whether they’ll be willing to dig deeper into those large savings accumulated in the last year, especially given the uncertain economic outlook not just in their home country, but globally. In addition, there develops a big conundrum as to whether the Bank of England should continue to cut interest rates when we’re expecting inflation to trend upwards by almost 1% over the next six months? But this is not to forget the Trump tariff risk…

Trump’s Tariff Leniency Toward the UK

‘Liberation Day’ on Wednesday (2nd April) marked a significant shift under President Trump’s administration and involved the introduction of sweeping tariffs on imported goods, in a bid to reduce the US trade deficit and promote domestic manufacturing. A Reuters roundup detailed Trump’s new baseline 10% tariff on goods from all countries globally, plus reciprocal tariffs on those his administration perceive have high barriers to US imports, such as 125% on Chinese imports – which China has since retaliated with 84% levies on the US.

Whilst the UK has avoided the 20% tariff blow faced by the EU, their economic outlook for 2025 has worsened, having now been disrupted by the global 10% levy. Reporting by Romei and colleagues in the FT suggests this rekindles concerns for Reeves as the slower economic growth from these tariffs will likely eat into her already limited fiscal headroom, imposing further pressure on the Chancellor to abandon her early fiscal promises and proceed to raise taxes later this year. Sir Keir Starmer aims to steer clear of retaliatory tariffs, as the UK works towards reaching a compromise with the US to reduce the imposed tariffs.

However, it can be argued that given the UK has come off relatively lightly compared to its international counterparts, upsides could emerge where manufacturing in the UK, potentially, just became 10% more competitive than the EU and other damaged countries, as suggested by James Leng in the FT. Yet pressure will still mount if Starmer’s anticipated US-UK trade agreement fails to materialise in the near future, as the tariffs are heavily inflationary and could therefore dampen British exports and the economy overall.

To conclude, the UK’s economic outlook remains precarious as Chancellor Rachel Reeves must navigate a narrow fiscal path riddled with obstacles. While her Spring Statement introduces measures aimed at stabilising public finances, the combination of inflation expectations trending upwards, constrained fiscal headroom, and the multifaceted troubles of external pressures from Trump’s global trade war leaves little room for error. Reeves’ ability to balance fiscal prudence with economic growth will be critical in the coming years, as the UK contends with its growing debt burden and sluggish recovery.