Following the Second World War, Japan achieved a remarkable economic growth, during the recovery period (1945-1956) they managed to average a 7.1% annual GDP growth. Recovery was then followed by an era of rapid growth, and Japan was finally closing in on western economies.

However, this unprecedented growth quickly turned into a bubble. Japanese people started living in the bubble economy era, baburu keiki in Japanese. This bubble can be retraced through the boom in prices in the housing market, such that, at the end of the decade, Kindleberger and Glibber (2011, p.173) noted that “the land under the Imperial Palace was greater than the market value of all the real estate in California”. While looking in depth into the reasons behind this asset bubble, we realise that an innovation by the name of Zaitech could explain the reason for its subsequent collapse.

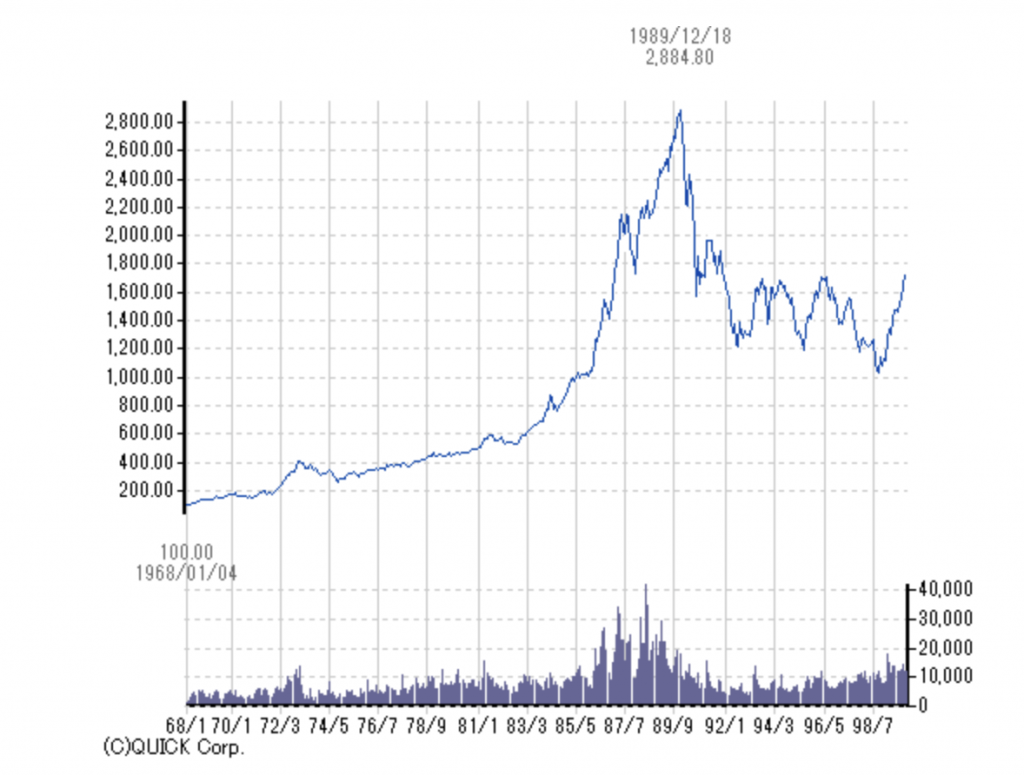

Zaitech is essentially a form of financial engineering, consisting of corporate speculation, facilitated by the emergence of another innovation, tokkin accounts, which according to Chancellor (2000, p.290) “allowed companies to trade securities without paying capital gains tax on it”. This created a financial system where profits were driven by speculative investments made by Japanese firms in the stock market. As these investments were made with “cheap capital” supplied by the increase in land prices, indexes such as the TOPIX were driven to all time highs in December 1989 as shown in Figure 1 (Japan Exchange Group, 2023).

Figure 1: Price and trading volume in billion JPY of TOPIX index (1968 – 2000)

The New York Times (1986) stated three years before the asset price crash that, “fund managers [in the tokkin management department] often chose speculative stocks”, and this frantic search for speculation led companies to increase their shares prices, causing an increase in the profit supplied by the Zaitech they used, while the profits from their off-trading activities started declining. This had such an effect in the increase in the price of the housing market, that it became hard to become a homeowner in Japan. Some banks even developed three generation mortgages that lasted “a hundred years” as mentioned by Kindleberger and Glibber (2011, p.176), which eroded the Japanese social harmony. This forced Bank of Japan to react by instructing Japanese banks to limit the rate of growth of their real estate loans, increasing the amount of property being sold. However, these distressed sales caused the price of real estate to decline, causing banks capital to decrease, leading to a fall in their stock prices, and therefore the profits from financial engineering and Zaitech to disappear.

This prompted a crash in the valuations of Japanese corporations that took part in financial speculation who lost their financing power. This resulted in Bank of Japan needing to lower their interest rates.

However, companies did not refinance through loans by taking advantage of low interest rates, instead Japanese banks decided to balance out their loss in capital through a decrease in their debt, as show by the economist Richard Koo (2009). This balance sheet recession still has an impact on Japan’s economy today as the country is struggling to have a sustained growth in GDP and stable inflation. This is due to low interest rates that the Bank of Japan can not seem to increase, or to quote David Pilling (2014, p.144) “[Interest rates] had been stuck at zero almost constantly since the late 1990s.”