John Maynard Keynes famously argued for deficit spending when economies fell on hard times, leading an upheaval in the status quo of economic thought during the aftermath of the great depression. His advice on cutting these deficits when the economy is strong however seems to have been brushed aside, entrenching us in hard times and unprecedented levels of government debt. How did we let this happen? One of Europe’s major economic powers provides a compelling story of how debt can quickly get out of hand.

Along with France, the UK, US and Canada all feature in the catalogue of advanced economies whose national debt to GDP ratios have flirted with or breached the 100% mark in recent years. These debts are continuing to grow in prominence and so too are the voices condemning them, with plummeting public confidence manifesting itself through the major credit rating agencies.

As these deficits continue to grow, the cost of financing them behaves in a similar manner, leading to higher levels of borrowing and future costs for the government when the assets (bonds), sold to raise capital, require interest payments or mature. If this type of behaviour persists without appropriate fiscal planning and explanation, these agencies are going to get suspicious.

May provided a good example of this when Moody’s finally joined Fitch and S&P Global in downgrading the US government to an Aa1, citing limited budget flexibility along with years of deficits (2015, Moody’s). This is catastrophic for a country that consistently runs such high deficits. The reduced perceived quality of treasury bonds is likely to drive up debt interest payments, grossly exacerbating the difficulty of financing a debt which already seems insurmountable. Recent reports suggest that this debt is now reaching heights of $37.8 trillion (US Treasury Fiscal Data, 2025), with its boundaries already being tested further by Donald Trump’s ‘Big Beautiful Bill’.

While France narrowly escaped a similar fate in March of this year (Leali G. 2025, politico), September saw the crown slip as Fitch downgraded l’Hexagone’s creditworthiness to A+ (the fifth notch on their scale) from the AA- that the country was clinging onto, signifying an exacerbation of the already-perilous budgetary difficulties faced by President Macron. Indeed, the budget has been a central theme of public discourse and a major source of political strife across the country for some time. Since the President called an ill-fated snap election in the summer of 2024 which left his party and its centrist allies as one of three similar-sized blocs in the French National Assembly, a loud, expensive game of tug of war over the direction of fiscal policy has been played between the in-power government and its critics and political opponents.

Before discussing today’s struggles however, we must return to 2008, when government debt truly exploded, to retrace the steps along the grim path that led one of Europe’s giants to near-calamity.

France’s Statist Response the Financial Crisis

During the pandemonium of job and home losses that was the 2007-8 financial crisis, mass bailouts for banks and financial institutions were necessary to keep financial sectors afloat. When combined with tax cuts and heavy social spending to ease the pain for households, it wreaked havoc on government finances across advanced economies. France was no different and was early in its introduction of a stimulus package for French businesses, putting in place a sovereign wealth fund that would support domestic companies (Levy J.D. 2017). While this particular move was on-brand for the then-president, Nicolas Sarkozy, who was far more immersed in the business world than his recent predecessors (Knapp A. 2013), it marked a stark shift from the prevailing neoliberal model of the time.

It is rare that a right-wing president such as Sarkozy, who had previously advocated economic liberalism, would be in position to denounce it, yet the political rhetoric that ensued seemed eerily familiar. This global breakdown lent itself to a return of the French post-war tradition of statism or “dirigisme”.

This was a style of governance that came to fruition at a desperate time for the French. After the dated, authoritarian failures of the 1940s Vichy Republic, post-war France committed to a program of state-led modernisation, reconstruction and interventionism, with the government taking charge of the direction of national industry. This resulted in a period of industrial and economic success which would become known as “les trente glorieuses”. Although this era had run its course by the 70s and 80s, a nostalgic sense of national pride surrounds those years and their fruits such as France’s high social security and labour protections (Woll C. 2008). At the same time, this brings about a disdain for modern, comparably ineffective and incompetent governments, perhaps explaining how it was so easy for Sarkozy to get wrapped up in his new dirigiste mantle and why the public angered when it didn’t last.

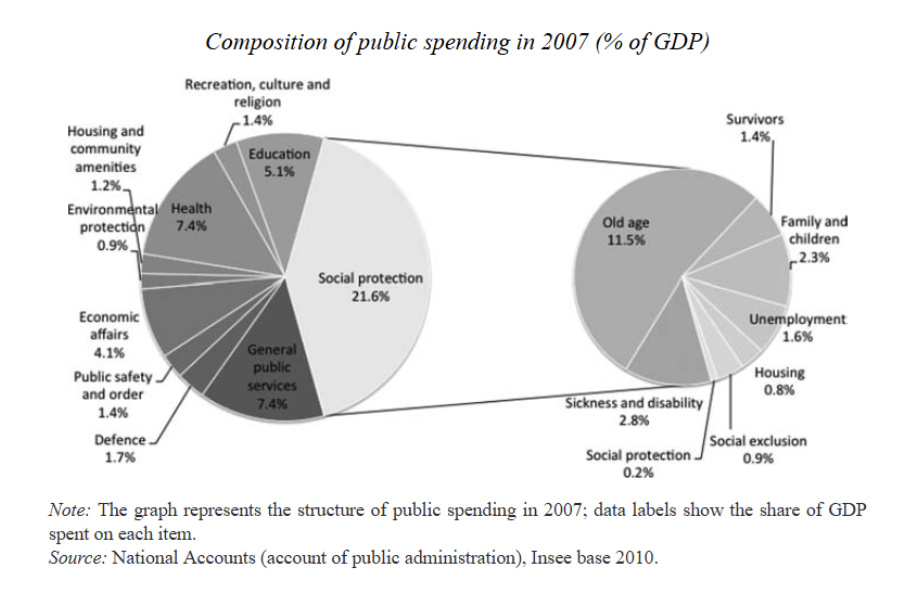

These social protections were still evident at the dawn of the financial crisis. French government spending was already high, with social security playing a major role, as seen in the figure below.

While it had led to deficits of around 1-3% being run over the 2000s, the robustness of this social safety net managed to somewhat soften what the blow on French households could have been, when compared with the effects felt by its neighbours. Therefore, when a fiscal stimulus package was brought in, it appeared to be comparatively modest. The same phrasing, however, could not be used to describe the weight given to investment spending.

Investment at odds with Welfare

The ‘golden rule’ of fiscal policy, the notion that governments should borrow only to invest, had been rearing its head in academic and political circles for some time. Sarkozy invoked this ‘rule’ in his sweeping 26-billion-euro stimulus package which was announced in December of 2008 and then later with initiatives such as the “Grand emprunt national” (great national loan). Heavily skewed towards industrial, research and business investment, the French government bucked the trend of prioritising demand-based stimulus and instead sought to revitalise its floundering industries that had been on the decline even before the crash. From 1997 to 2012, the country would experience a 38% drop in its share in global export markets (Charlet V. et al, 2023). While this trend was not dissimilar to the experience of its neighbours, it was still alarming.

The president was adamant that the liabilities created to fund this investment would become assets and the short-term fiscal hit would soon subside as investments brought in returns and the economy grew. Nevertheless, national debt was growing, and people weren’t seeing much improvement in their day-to-day lives given the seemingly stagnant state of the welfare system as well as the initiative of investing for the future. Sarkozy continued to hammer home his support for investment spending which brought with it a certain denigration of other forms of public expenditure. “Operational” current spending was vilified as austerity measures began to wash up on European shores during the early 2010s. Welfare and social schemes were either cut or underfunded, with those few initiatives that made it through the cracks delivering a fraction of their billing; approximately 6% of the target amount of recipients (160,000) benefitted from a social welfare benefit, aimed at aiding destitute young people in a harsh labour market (Pickard S. 2012).

In spite of these cuts, French national debt had risen to almost 90% of GDP by 2012 along with sluggish growth, leaving Francois Hollande, a traditionally left-leaning president, and his string of prime ministers and governments a mandate of fiscal responsibility while stepping away from the austerity measures that had engulfed Europe (Lepont U. 2023). A difficult balance to achieve. While there were some headline measures such as a 75% income tax for those earning above 1 million euros, the president’s aversion to austerity as a deficit reduction tool did not last all too long. By 2014, the newly dubbed “Francois Blair” (courtesy of the French communist party) was announcing a 2-year plan to cut 50 billion euros of spending (Ball S. 2014, france24). Pro-business measures soon followed suit with tax cuts and an expansion of Sarkozy’s investments for the future program. All in all, not a lot had changed: national debt kept rising, deficits persisted, and public trust in government economic management was eroded.

Budgets and Political Deadlock

When Emmanuel Macron came to power in 2017, the scars of the financial crisis were still raw. The new centre-right leader’s goals of modernising the French economy through investment in startups and reining in public finances has continually put the government at odds with the public. A controversial pension reform, aiming to raise the state pension age from 62 to 64 was notably met with mass protests in 2023. Difficulty pushing such reforms through has blighted Macron’s deficit-slashing plans, leading to a predicament that has only been exacerbated by the excessive spending required during the COVID-19 pandemic. Surges in energy prices over 2022-23 pushed budget concerns further from public conscience as the need for subsidies took precedence as Macron took a “whatever it takes” attitude in response to these crises.

However, by 2024, the familiar fiscal woes were front page news again with the budget deficit reaching 6.1%, up from 5.45% the previous year. This far exceeded the 3% limit stated in the terms of the EU’s growth and stability pact. More concerning is the political fragmentation that had taken over the French national assembly. Shock results in the summer’s European elections, which were diagnostic of Macron’s diminishing popularity, saw the far-right Rassemblement National double the number of seats won by the president’s centrist bloc. A snap election was called. Billed as the only democratic thing to do, it could be said that this was a political Hail Mary from Macron as he sought to consolidate power for his allies in the national assembly after 2 years of arduous governance at the head of a government which had lost its majority in the 2022 legislative elections. During this time, the controversial article 49.3, which allows the in-power government to bypass the assembly to pass a bill, had been used over 20 times. Msr. Macron now hoped that national fear of RN gaining power would swing votes in his favour and parliamentary processes would become smoother. It goes without saying that this did not go to plan. This snap election resulted in major losses for Macron’s allies and record gains for RN as well as the left-wing coalition NUPES, leaving him with a minority coalition government if he wanted one of his own as prime minister.

As summer drew to a close and the days became shorter, President Macron found himself sinking into an abyss of problems. His party had lost power in the European parliament, his national assembly was in disarray, and he was under immense pressure from Brussels to sort out his country’s finances. He turned to seasoned politician and former Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier as a PM appointment with the principal aim of getting a budget through parliament which could put a dent in the deficit. Msr. Barnier attempted to do just that, proposing a budget which aimed to improve the government’s fiscal position by 60 billion euros. Unsurprisingly, this was attacked from all angles. Both sides of the political spectrum were angry at the spending cuts and the effects they would have on the French public, while jointly adamant that Macron should not have appointed one of his own allies given the results of the election.

Barnier was unceremoniously ousted after just 90 days in office after his attempt to push through his budget via article 49.3 resulted in a vote of no confidence, wrapping up the shortest term of any prime minister in the history of the 5th Republic. This spoke volumes to the level of political fragmentation in France. It also ramped up the panic surrounding their budgetary difficulties. According to the freshly unemployed Michel Barnier, debt interest payments were now mounting to levels that exceeded the national defence or education budgets as Moody’s downgraded the country’s creditworthiness to round off the year.

The next prime minister, Francois Bayrou, came into office with a similar mandate. He opted for a slightly less ambitious, and more hastily put-together proposal to Barnier’s, though still included one-off taxes, public expenditure cuts and welfare payment freezes. His use of the ever-popular article 49.3 inevitably led to intense criticism, particularly from left-wing firebrand, Jean-Luc Melenchon who condemned this budget as ‘worse than Barnier’s’ in a barrage of public statements and rapidly motioned for votes of no confidence to topple Bayrou’s government.

While most other opponents were still opposed to the contents of this somewhat cursory proposal, the desperation for some stability and an official budget for a year about to enter its third month had grown. Doubts and divisions were momentarily repressed as Bayrou managed to secure the backing of the socialist party (france24). The Prime Minister and President alike breathed a sigh of relief. While this moment led parliament into a period of comparative calm (at least concerning fiscal policy), leading economists such as Olivier Blanchard (previously chief economist at the IMF) stated that this budget won’t be enough to stop France from hurtling towards a crash (Leali G. 2025).

The calm couldn’t last long though. Come summer, Bayrou began to unveil his plans for the 2026 budget, which of course involved more of the same; pension and healthcare spending cuts were the oft-highlighted elements of a budget seeking to cut spending by 44bn over three years (Le Monde). On this occasion, there was no desperation amongst those in parliament to keep Bayrou in power and push through an austerity plan. The Prime Minister himself called a confidence vote, staking his government’s political survival on the budget. He was met with a resounding majority of 364 lawmakers voting against him, ousting the government after only 9 months.

Plunged into chaos and crisis once more, calls for another snap legislative election or even for the President himself to step down were heard amongst political opponents of Macron. Instead, another ally of his was named as Bayrou’s replacement.

Sebastien Lecornu has taken the reigns and attempted to cast a wider net concerning negotiation by completely ruling out any use of Article 49.3. This has been heralded as a great concession by his closest allies. While it was cautiously welcomed by the socialist party, there are still looming concerns in this camp over the resistance to a reopening of debates on pension reforms.

While Lecornu has promised a break from the past, it is difficult to see where this break will come from. Despite his comparative youth, he comes from a similar centrist tradition to his predecessors and is faced with the seemingly inconceivable task of restoring balance to public finances in the most unforgiving of political climates. His attempts to build cross-party bridges are promising but since they already seem to be crumbling, getting a deficit-reducing budget through is already shaping up to be another gauntlet of public disapproval and votes of no confidence.