The Economic Impact of Sanctions on Iran: A Quantitative and Image Based Analysis of Growth

Iran has historically been a closed, centralised, yet industrialised economy, with most of its capital and human capital gravitating to the energy extraction industry. It is the ninth largest producer of oil in the world. Iran’s production of oil and gas is technologically comparable to its Middle Eastern counterparts, as well as global leaders such as Russia and Norway. However, it is significantly less efficient due to lack of market competition within the country, as its industry is nationalised. This structure has led to corruption; most decisions around contracts, strategy and operations are political rather than business motivated. Given this inefficiency, Iran is estimated to profit 70 cents per barrel for every dollar earned by its competitors. Alongside its energy industry, Iran has several adjacent industries, such as industrial manufacturing, often as a function of its extraction operations. Due to the Supreme Leader’s dictatorial and nationalist pursuit of complete self-sufficiency, Iran faces constraints in importing its manufacturing goods for heavy industry required for a large-scale extraction of natural resources. As a result, it is forced to spend more than market price on industrial equipment and facilities to extract and refine oil. Therefore, most of its economic activity is in oil-adjacent industries that serve the facilitation of extraction of the country’s natural resources. Much of this industrial manufacturing doubles as infrastructure used for its defense manufacturing, which is also homegrown. In addition, due to its aversion to trade, Iran is forced to use much of its energy in the form of oil and gas to drive its growth through industrial production, making it the Middle East’s largest exporter and consumer per capita of oil.

Given Iran and the United States’ geopolitical tensions, it is natural that the two nations are not cooperative and aligned in trade policy. However, given the two nations’ active undermining of each other’s objectives, trade has ceased to a near full stop for several periods in the past 30 years. Ever since the Islamic Revolution of 1979, in which the U.S. backed government was overthrown in a dramatic rejection of westernisation and affinity to democratic and free market ideals, Iran has fought western interests through indirect proxy groups which it supports through aid, intelligence, training and weapons. In the early 1980s, this practice began through the support of Lebanese Shia militias, which through training by selected units of Iran’s special forces, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, became what is now Hezbollah, a terrorist organisation which has plagued American forces and Israel for years. Later that same decade, Iran began its support of groups such as Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, which also violently opposed a Western and Israeli presence in the region, and any of its sympathisers. After the 1990s and in 2011, Iran backed groups such as Asaib Ahl al-Haq in the U.S. military campaign in Iraq, and the Assad regime in Syria. Through the funding of proxy groups in the Middle East, Iran is able to use insidious insurgency warfare by militias as opposed to a more costly open war with the west.

Because of its violent antagonism to American interests, Iran has become a target of sanctions and other related trade restrictions, in an attempt to economically punish the country and by consequence sway popular opinion and leadership. The first sanctions were put in place during the Carter administration following an occupation of an American embassy by Iranian protesters. This embargo froze 12 million dollars in Iranian assets in the U.S., only targeting nationalized investment funds and government and corporate assets. Throughout the next two decades, the United States placed much broader, harsher sanctions in place, restricting the Iranian banking sector, blocking imports of Iranian oil as well as industrial machinery and equipment. Much of the motivation for these sanctions was to thwart and deter Iran’ s nuclear ambitions, which would allow for a profoundly anti-Western country to leverage nuclear war in negotiations as well as a weapon of war. This prospect became the primary focus of sanctions in the early 2000s onwards, as the threat of nuclear war dwarfed the inconvenience of insurgency campaigns in the Middle East.

The primary purpose of sanctions economically is to isolate the subject country from a broad swath of trade clients, which allows for the smaller market share that does not apply sanctions to charge significantly more than market price for goods imported and exported, having an oligopoly. Additionally, investments and trade infrastructure already in place at the time of sanctions would have to be utilized, yet would be forced to do so at a higher price if sanctions were to be partial in the form of tariffs, or would go to waste if sanctions were complete. Iranian factories with American companies as their primary exports and with offices and deals with American clients would be forced to shut down operations if complete sanctions were placed on their sector. Any ongoing investments in large infrastructure projects that rely on the guaranteed future revenue would become significantly riskier, as large down payments in the Iranian economy would be in constant jeopardy of default. International investment is reduced, as the subject country appears less reliable for revenue. Any investment in the form of loans and bonds that the subject country receives would be paid at a significantly higher interest rate due to risk of default as well.

In part, American leaders and policy makers refused to engage in commerce and mutual economic betterment with Iran due to moral and idealistic reservations. And in part, they believed that sanctions on Iran had the capacity to weaken the domestic economy and impact Iran’s ability to continue to pursue expensive labor and capital intensive projects such as a nuclear program and aid to terrorist groups. In addition to weakening Iran’s ability to fund its infrastructure investments, policy makers believed that economic downturn as a result of embargoes could result in public discontent with the Iranian government and destabilise authority, mitigating the threat of a united, prosperous, and aggressive Iran. Into the early 2000s, these sanctions continued. Yet, they began to double down on prevention and deterrence of the nuclear program, paired with a campaign of disruption on Iranian efforts to develop nuclear weapons, assisted by Israeli intelligence services, notably killing prominent nuclear scientists and striking nuclear facilities.

During the early 2000s, the UN joined American efforts to isolate Iran, placing heavy sanctions on Iranian oil, finance, and industry, with a focus on arms exports, which were banned. The industry for nuclear weapons development was naturally the target of western sanctions, yet adjacent industries which could have been beneficial to the development of nuclear weapons, through support and funding, were sanctioned. Iran, during this time, continued to produce and export to other Middle Eastern countries, Russia, as well as some African and South Asian countries. Exports were controlled manually by Iran’s highest leadership, and used a case-by-case contract basis, in which deals for export of industrial goods, oil, and most notoriously weapons, were brokered. Oftentimes arms exports were transferred from Iran to other regimes, or at times to opposition groups and militias attempting to destabilise or challenge existing regimes. Iran, at the time, exported its largest quantity of weapons to the Assad regime in Syria, as well as warlords in the Ivory Coast, Guinea, and Sudan.

In 2012, the Iranian Threat Reduction Act enacted further sanctions on a broader array of Iranian industries, this time restricting aerospace research and development, not limited to manufacturing and export. These sanctions also targeted Iranian financial funds more aggressively, which led to major global banks and investment funds de-investing from Iran, pulling funds and financial capital from the country. These sanctions were placed during the Obama administration in an attempt to revamp the American approach to Iran, not limited to restrictions on military exports, but rather a holistic reduction of Iran’s ability to develop, fund, and manufacture infrastructure to develop a modernized military equipped with nuclear weapons. At the end of the Obama administration in late 2015, sanctions on non-military infrastructure were lifted, in return for a monitored end to the nuclear program, verified by a third party organisation. This deal leveraged the economic power yielded by the sanctions for the U.S. to change Iran’s strategy in pursuing a nuclear arsenal. The deal did not stop sanctions on many products, yet loosened the draconian embargo previously in place.

Following this period of generally staunch regulation, the Trump and Biden administrations frequently reversed decisions, often removing and re-applying sanctions. This frequent reversal of policy indicates an abandonment of the previous objective of long term erosion of Iran’s economic prowess through decades upon decades of commercial isolation, and instead shows a propensity by the federal government to use sanctions as a short term punishment, making a global statement and hurting exporters in Iran in the short run. The Obama Iranian Nuclear Deal in 2015 was the first and most effective example of this. This marks the reshaping of sanctions’ role in foreign policy, from a weapon of economic degradation to a threat whose expected consequences coerce adversaries to comply with American interests.

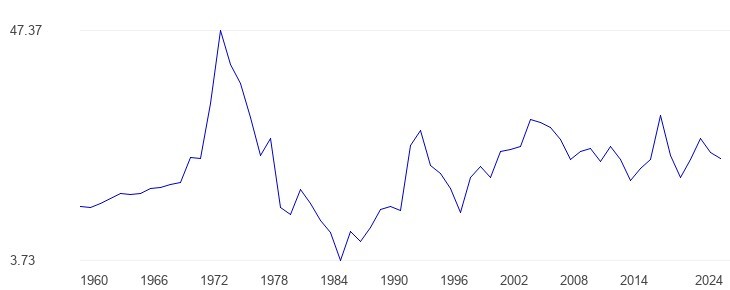

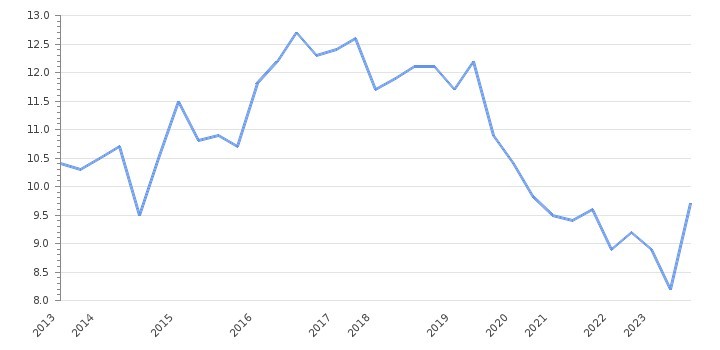

The impact of sanctions on macro indicators of economic wellbeing is mixed. GDP grew between the mid-1990s and 2007, in great part due to renewed demand in oil which Iran produced and exported regardless of the beginnings of sanctions. GDP naturally fell significantly following the 2008 financial crisis, yet rebounded in ebbs and flows for the next decade and a half (Figure 1). Sanctions being lifted through Obama’s Iran Nuclear Deal may explain the GDP skyrocketing in 2015 and 2016, yet other factors such as major Chinese investment in Iranian industry around this time may also be responsible for this. The unemployment rate rose for years following the 2008 financial crisis, and peaked from 2016 to late 2019. A steep decline followed in the next half decade (Figure 2).

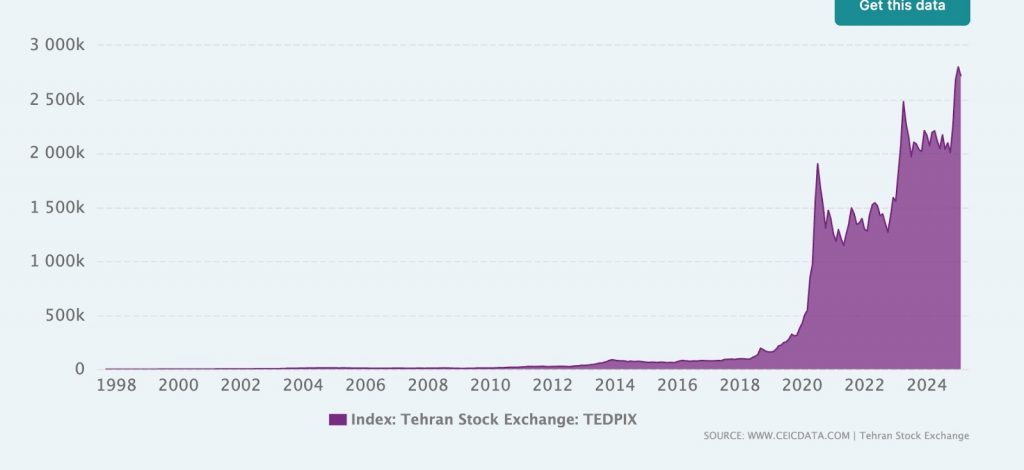

The unemployment rate matched regional and global trends, particularly in relation to demand for oil and natural gas. Unemployment in Iran is typically significantly higher than the global average due to the inefficiency of nationalised industry, so it is unlikely that sanctions are responsible for this. At the individual consumer level, the average MPC (Marginal Propensity to Consume) rose and fell throughout the course of sanctions, yet oil price declines coincidentally tended to match harsh sanction periods. Therefore, MPC on average was linked directly to sanctions with a six month delay, but was equally correlated to oil prices. Iran’s inflation rate spiked during times following heavy sanctions, as the cost of production, import, and distribution of goods inherently increased with the disruption. Sanctions can be assumed to be partially responsible for these spikes in inflation, and although inflation dropped following these spikes, deflation did not occur until a new trade partner was found. The national stock market (Tehran Stock Exchange) remained at low but stable valuation, as sanctions isolated Iran from foreign investment which for most markets drives growth and keeps value afloat (Figure 3).

Unlike most countries, Iran does not publicise many of these metrics, and internal inquiries are heavily monitored and censored to benefit the Supreme Leader and public image. The majority of metrics on Iran’s economic health are determined by estimates by “basket of goods” assessments on the ground for MPC and inflation calculations, as well as import and export estimates using port entry records and satellite imagery for economic activity. GDP is also estimated through similar means. Many of these statistics are thus estimates and heavily approximative, and are imperfect when trying to isolate the impact of a specific variable of economic growth such as sanctions. Additionally, even with accurate data on macro indicators, to measure the exact impact of sanctions, external economic factors must be removed.

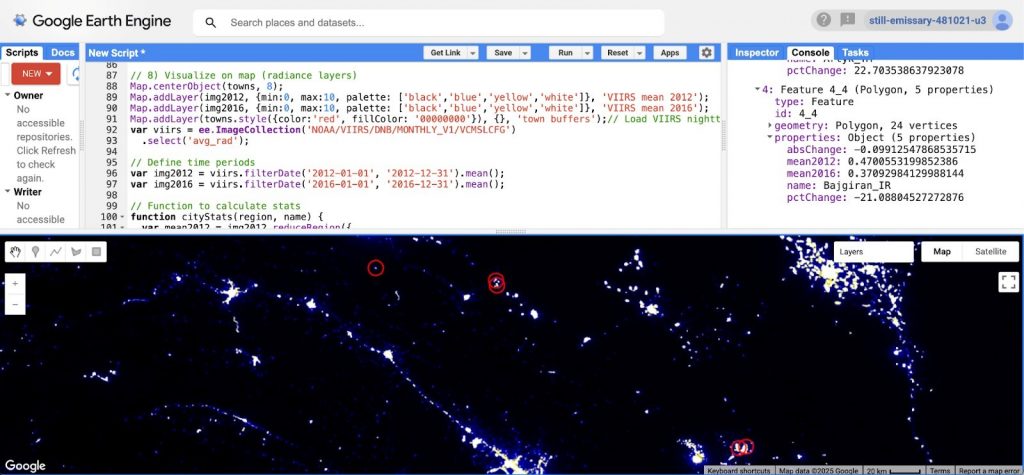

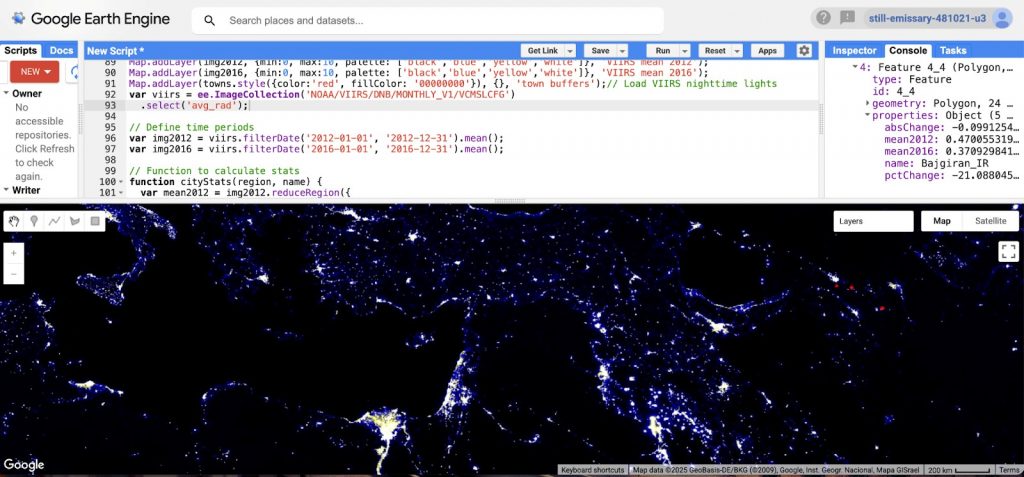

To supplement macro estimates of data, I gathered satellite data through Google Earth Engine nighttime historical imagery, a backroom extension to Google Earth, with open Javascript code, modifiable to analyze the image data. After downloading data from the Middle East region (Figure 4), I used Chat GPT to help me instruct the engine through Javascript to compare the difference in light pollution trends over time between border towns in between Turkmenistan and Iran (Figure 5). Light pollution is a commonly used metric to track economic growth, as it encompasses population growth, infrastructure development, and consumption of energy. More light in an area almost always equates to economic growth, although the production of light is a byproduct of an array of factors. A measurement of light pollution in major Iranian cities over the course of sanction’s effects could yield a net trend of growth, yet sanctions are one of many possible causes for the growth or lack thereof. To control for these external factors, I compared light pollution in border towns of Iran and Turkmenistan. For each Iranian town I analysed light pollution, I analysed a corresponding Turkmenistani town with similar industries, population, and demographic buildup, within 15 miles of each other. Although Turkmenistan and Iran are different countries with different economic, social and political structures, of all Iran’s bordering countries Turkmenistan is the most similar. This is through its relatively diversified and closed industrial economy founded on energy export, and its dictatorial leader in charge of all decision making. Unlike other bordering countries, Turkmenistan shares Iran’s relatively cutting edge industrial prowess and innovation, yet like Iran, its institutions function inefficiently and with some corruption.

Towns on the border at such close proximity have differences, but have many more similarities, making them the best comparison for the effect of sanctions. The primary difference between the Turkmenistani and Iranian towns is the absence or presence of sanctions. Available data in Google Earth Engine spans from 2012 to 2016, and given existing research on sanctions’ greatest impacts being over long periods of time, I used each extremity of time as comparison. During these four years, the Obama administration intensified sanctions on Iran, expanding existing military and industrial boycotts to the targeting of financial assets. Although the severity of sanctions at the beginning of our observation in 2012 significantly increased, I am assuming that sanctions do not have diminishing returns, in which the first set of sanctions has significantly greater impact than later sanctions. I am also assuming that there are not significant changes in trends of light pollution leading up to 2012, which would be continued in the data. To control for some of these existing trends, I also recorded the difference in light pollution over the same period of similarly sized towns, hundreds of miles from the border in inland Turkmenistan and Iran. These towns give a comparison of expected change in light pollution outside of the analysed area and control for regional differences and other existing trends.

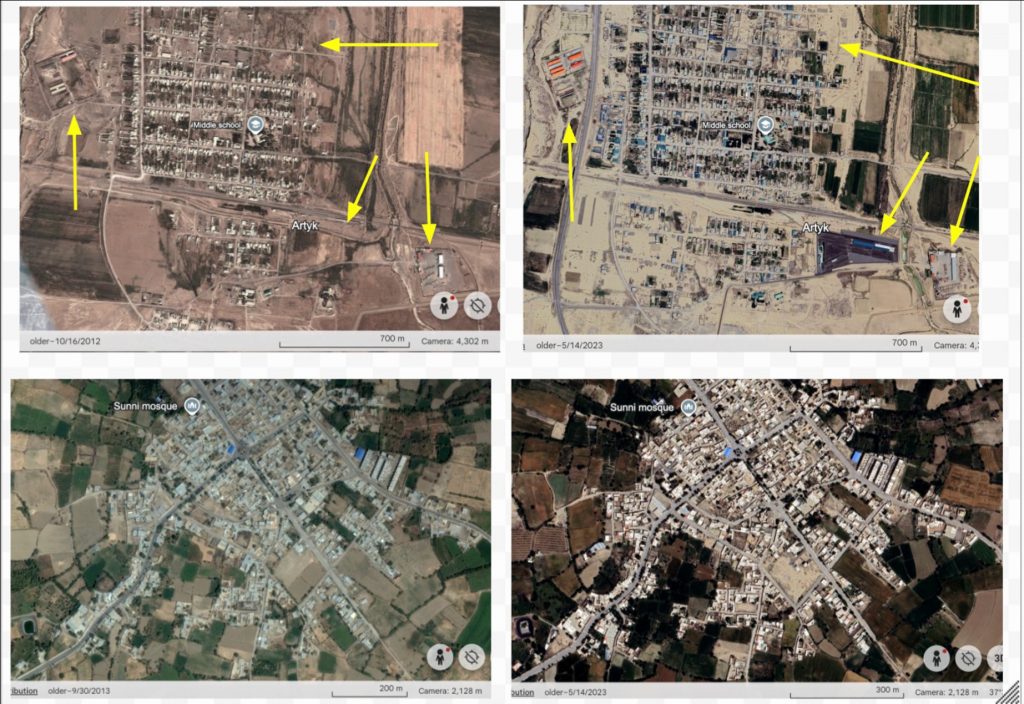

Google Earth Engine, following my instructions, analysed the change in brightness of pixels in the coordinates of towns on the Iranian-Turkmenistani border from 2012 to 2016. Results were mixed, with one pair in Iranian Sarakhs and Turkmenistani Serakhs indicating a decline in both towns, yet the Turkmenistani side experienced ten times more decline, 8% as compared to 0.8% for the Iranian side. The next pair showed the opposite, the Turkmenistani town of Artyk experiencing a 22% increase in light pollution while its corresponding Iranian town of Bajgiran saw its already dim light profile drop by 21%. A third pair was dismissed as an outlier, as Iranian Loftabad saw a relocation of a textile plant from a nearby town which skewed its light pollution results. The independent towns outside of the region recorded showed similar trends to the border town in Turkmenistan, displaying moderate growth, while the towns in Iran remained stable.

Although the results of the experiment are near net zero, due to the two pairs cancelling each other out, under further scrutiny I identified the towns in Turkmenistan that saw an increase in light as having new industrial developments, while the town in Iran which experienced a light pollution spike saw no industrial development and no construction. I was able to make this determination through daytime satellite imagery comparison for these towns, comparing 2012 aerial images of the town to 2016 and present day images (Figure 6). Due to the high fluctuation of Iran’s average MPC regionally discussed previously, it is possible that in some Iranian towns observed as having significantly increased light pollution, MPC was by chance higher than the mean at the time of recording of the image, or other short term independent economic stimulus caused the light pollution increase. This indicates that growth at the consumer level in the form of small businesses and energy expenses was relatively unaffected by the sanctions, while industrial production accounted for a decline in expected growth. Growth overall did not greatly differ as a result of sanctions, and swells in consumer expenditure local economic activity kept overall economic activity comparable to Turkmenistan, yet everything else constant the Iranian economy was weakened. A decline in economic activity in industrial towns is detrimental to Iran’s growth long term, as a decline in its driving sector for growth can not be canceled out by growth in services industries in adjacent towns. This is because similar light pollution readings do not differentiate between themselves on their own yet are different between each other. An 18% increase in economic activity in Loftabad does not equate to a hypothetical 18% increase in activity in an industrial Iranian town, as industrial investment will yield long term growth for all of Iran and attract more foreign investment, while increased consumer spending on produce and energy is temporarily stimulating for the national economy.

When assessing the success of U.S. sanctions on Iran, the results are multiple. In the objective of the U.S. of hurting the Iranian economy in consumption and subsequent ability to leverage assets to raise capital, there is not a significant measurable effect in the decade following a sanction. In the short term, inflation spikes, yet deflation can be expected once a non-sanctioning nation is found as a trade partner. It is unlikely that these varied and non devastating results for consumers would result in a break in national identity and allegiance to the supreme leader and even less likely would result in an uprising or destabilisation of the regime. However, my findings show that a lack of industrial activity in in towns that rely and carry Iran’s industry is a result of sanctions, so the long term geopolitical game of chess, the U.S.’s sanctions do weaken Iran’s ability to sustainably fund and develop its industry, and thus sanctions hurt the health of Iran’s driving industry.

As a weaker Iran is an objective of the U.S., sanctions do play into American hands, although this is possible only if those sanctions are consistent for long periods of time, enough time to erode Iran’s economy and weaken its foundations. With frequent transitions of power and visions for American presence and intervention in the Middle East, long term economic erosion through internationally united abstinence to trade with adversaries is difficult, but would yield the primary benefit of sanctions. Lastly, sanctions’ potential for economic decline has enabled their use as leverage in diplomacy, as used in the Iranian Nuclear Deal during the Obama administration in 2015, yet a removal of sanctions in return for change in political strategy does affect the consistency of sanctions and hence their economically erosive nature.

Figure 1: Iranian GDP over time.

Figure 2: Iranian unemployment rate over the years.

Figure 3: Iranian primary stock exchange market (TEDPIX) valuation over time.

Figure 4: Google Earth Engine analysis in Javascript of light pollution in border towns between Iran and Turkmenistan.

Figure 5: Google Earth Engine analysis in Javascript of light pollution in Middle East.

Figure 6: Satellite imagery between approximately 2012-13 and 2016-24 in Artyk, Turkmenistan (top) and Loftabad, Iran (bottom), arrows indicating new industrial construction.

Works Cited:

Aminifard, A. (n.d.). The effect of sanctions on Iran’s economy: Solutions and prospects .

Department of Economics, Islamic Azad University, Shiraz, Iran. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep20927.8

CEIC. (n.d.). Iran equity market index. https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/iran/equity-market-index

Google Earth Engine. (2025). Google Earth Engine [Data platform]. Google. https://earthengine.google.com/

Rafique, N., & Shah, B. (n.d.). Political and economic impact of nuclear-related sanctions on

Iran and its foreign policy options. Strategic Studies . https://www.jstor.org/stable/48527622

Singh, M. (n.d.). Iran and America: The impasse continues. Horizons: Journal of International

Relations and Sustainable Development . https://www.jstor.org/stable/48573756

The Global Economy. (2025). Iran exports, percent of GDP . https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Iran/exports

[1] “Iran Exports, Percent of GDP,” The Global Economy, accessed December 14, 2025, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Iran/exports/ ; Michael Singh, “Iran and America: The Impasse Continues,” Horizons: Journal of International Relations and Sustainable Development , https://www.jstor.org/stable/48573756 .

[2] . Abbas Aminifard, “The Effect of Sanctions on Iran’s Economy: Solutions and Prospects,”

Department of Economics Islamic Azad Shiraz University, Iran , https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep20927.8 .; Singh, “Iran and America 3

Najam Rafique and Babar Shah, “Political and economic impact of nuclear -related sanctions on Iran and its foreign policy options,” Strategic Studies, https://www.jstor.org/stable/48527622.

[3] Rafique and Shah, “Political and economic.”

[4] Rafique and Shah, “Political and economic”; Aminifard, “The Effect”; Singh, “Iran and America.”. 6

Rafique and Shah, “Political and economic,”

[5] Rafique and Shah, “Political and economic,”. ; Aminifard, “The Effect,” ; “Iran Equity Market Index,” CEIC, https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/iran/equity-market-index . ; “Iran Exports,” The Global Economy.

Aminifard, “The Effect,” ; Singh, “Iran and America,”

Singh, “Iran and America” ; Google Earth Engine Powered by Google Cloud Infrastructure , Google Earth Engine, accessed December 14, 2025, https://earthengine.google.com/.