Thames Water, the largest water company in the UK, serving 16 million people, is currently facing a significant solvency crisis. The company is burdened with a substantial £19 billion debt and risks running out of cash by Christmas.

Before we dive into this topic, let me share my initial thoughts on water companies. The water industry should be a relatively stable business. It operates as an oligopoly in England and Wales, with only eleven companies serving these regions. In some areas, water companies even enjoy monopoly-like benefits, as it is uncommon for multiple providers to serve the same location. The market has high entry barriers due to the substantial infrastructure investments and regulatory approvals required. Demand for water services is also very stable, as water is an essential resource. Although factors like population growth and mobility can affect demand, these factors change slowly and are unlikely to result in significant variable costs for water companies. Therefore, when I first heard about Thames Water’s situation, I had several questions. Why does Thames Water carry such a large amount of debt? How has this debt been utilized?

In 2004, water bills increased by 20% following a new five-year price review. Since then, UK water companies have become attractive to financial buyers, in contrast to other utilities. In 2006, Macquarie, an Australian bank, acquired Thames Water from RWE, a German utility firm, for £8 billion. Other water companies, including Anglian, Southern Water, and Kelda Group, underwent similar acquisitions by financial buyers. Subsequently, these companies became “cash cows” for their private owners, often stripped of value and left weakened.

(Jack, 2024):

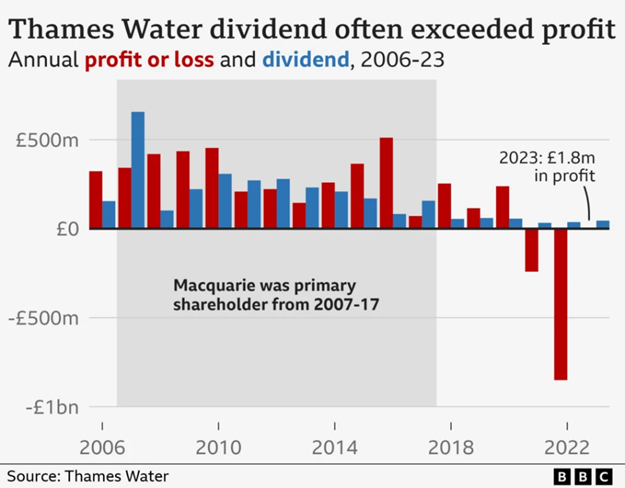

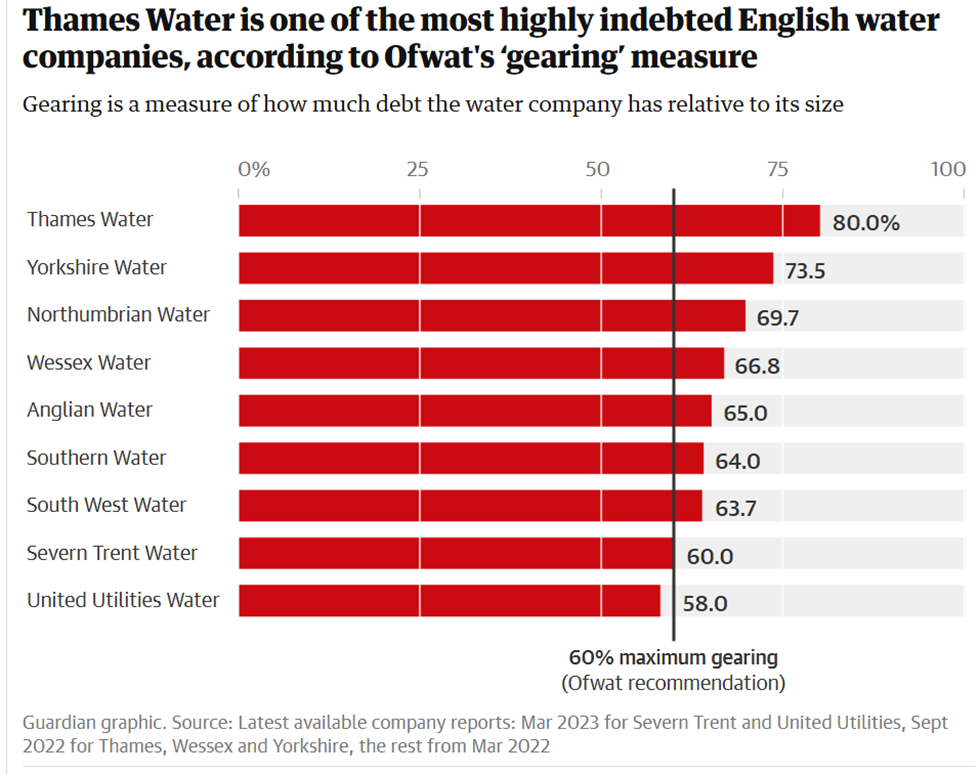

Macquarie held the majority share of Thames Water from 2007 to 2017. Under Macquarie’s ownership, the company issued a £656 million dividend in the first year, which even exceeded its profits. According to an analysis by The Guardian (Laville et al., 2023), around £2.8 billion in dividends was taken out during Macquarie’s ownership. To finance such large dividend payouts without sufficient profits, the company accumulated excessive debt. By the time Macquarie sold its shares, Thames Water’s financial position was dire. Its debt had increased from £3.4 billion in 2006 to £10.8 billion in 2017, resulting in a leverage ratio of 80%—well above the 60% ratio recommended by Ofwat.

(Laville et al., 2023):

Additionally, Macquarie implemented a strict cost-cutting policy at Thames Water, according to company veteran Cliff Roney, who spent four decades with the company (Isaac & Lawson, 2024). Many skills and services were outsourced to reduce costs, and essential chemicals were purchased only when absolutely necessary. These measures were not designed to reinvest in the company but to extract cash for dividends to shareholders. As a result, Thames Water not only accumulated a heavy debt burden but also suffered from poorly maintained and managed facilities. This mismanagement led to significant fines and prosecutions for pollution and damage, further weakening its financial position and reputation.

The regulator, Ofwat, was heavily criticized for not addressing Thames Water’s financial structure and dividend policies for over a decade. Only last year was it granted the power to intervene in the debt levels on water company balance sheets. Some argue that Ofwat focused too much on keeping bills low, neglecting the need to encourage investment (Jack, 2024). As a result, investors adopted an aggressive “looting” strategy to achieve returns.

Thames Water now holds £16 billion in debt, which was recently downgraded by S&P. Its Class A debt was downgraded from CCC+ to CC, and Class B debt from CCC- to C (Healy, 2024). There are a few potential solutions to alleviate its debt burden.

First, increasing customer bills to generate more revenue. In August, Thames Water requested a 59% increase in water bills over the next five years, although the regulator had initially proposed only a 23% rise in July (O. Smith, 2024). A final decision on water bill prices is expected by December.

Second, securing emergency loans from hedge funds and asset managers to keep operations running until Ofwat approves a bill increase. However, disputes have arisen over which debt proposal Thames Water should choose, particularly between Class A and B bondholders (Smith et al., 2024). One Class A bondholder, Elliott Management, a $70 billion US hedge fund, is willing to provide a £3 billion loan at nearly 10% annual interest, with additional fees if Thames Water repays the loan early, ahead of its 2.5-year maturity. Some believe the offer from Class A bondholders would extend the maturity date, giving Thames Water time to free up cash for repayments. Meanwhile, Class B holders offered a cheaper loan of the same amount at an 8% interest rate. However, since Class A holders own the majority of the debt, the proposal from Class B is less likely to receive approval. Alastair Cochran, Thames Water’s chief financial officer, stated that the Class B group’s proposal lacked sufficient detail to gain board support (Kleinman, 2024). Regardless of which proposal is accepted, Thames Water’s debt will continue to grow, potentially worsening its bond rating, increasing borrowing costs, and leading to a vicious cycle.

The third option, which bondholders are unlikely to support, is renationalization by the government, as this would result in significant losses for them.

From the public’s perspective, however, many people support the renationalization of the water industry. They view the privatization of essential infrastructure as a failure dating back to Margaret Thatcher’s administration in the 1980s.

References:

Healy, E. (2024, October 29). S&P downgrades Thames Water debt further into ‘junk’ territory. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/4c55608a-bfe2-4761-95e6-e8e57e4fdc94

Isaac, A., & Lawson, A. (2024, July 11). Debt, sewage and dividends: the rising tide of Thames Water’s troubles. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/article/2024/jul/11/debt-sewage-and-dividends-the-rising-tide-of-thames-waters-troubles

Jack, S. (2024, October 25). The water industry is in crisis. Can it be fixed? BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c0qdev4vyl5o#comments

Kleinman, M. (2024, November 7). Thames Water bondholders submit rival £3bn financing offer. Sky News. https://news.sky.com/story/thames-water-bondholders-submit-rival-3bn-financing-offer-13249806

Laville, S., Leach, A., & García, C. A. (2023, November 24). In charts: how privatisation drained Thames Water’s coffers. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/jun/30/in-charts-how-privatisation-drained-thames-waters-coffers

Smith, R., Plimmer, G., & Healy, E. (2024, November 10). How Thames Water became a battleground for hedge funds. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/508771ea-2d4f-420e-9631-4d9a1dcf8062

Smith, O. (2024, November 6). Water bill rises: Warning millions will struggle to pay. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/ce9gve1grjmo