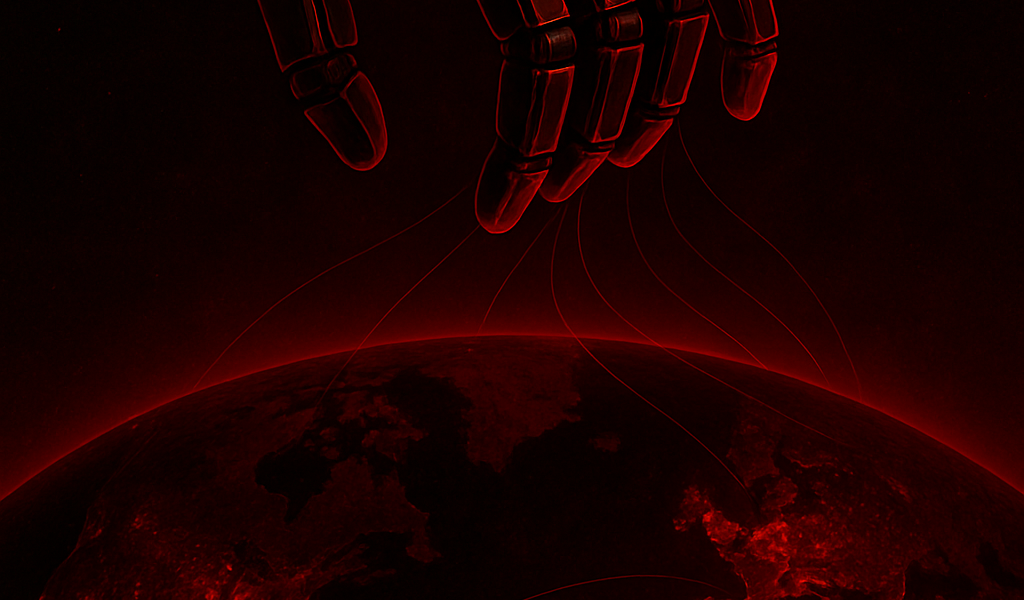

How Ready Are We for Extinction? The Political Economic Foundations of a Post-AGI World

Exeter Economics Review

Lorenzo Satta Chiris, Emil Archambeau, Francesca Mignogna

Abstract

The emergence of artificial general intelligence (AGI) promises to be the most transformative event in human, economic and political history. Capable of outperforming humans across cognitive tasks, AGI could either inaugurate a new era of abundance and innovation, or precipitate systemic collapse through mass displacement, inequality, and loss of control. As scalable cognitive labour removes the boundary between capital and intelligence, long-standing assumptions about production, scarcity and economic theory are challenged. This paper examines the implications of AGI as intelligence becomes a new and decisive factor of production, exploring how labour markets, economic and geopolitical structures could be permanently reshaped. We assess the risks of extreme concentration of wealth and influence, geopolitical inequalities, and the emergence of machine intelligence as scalable capital, an economic singularity.

Keywords: Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), Economic Theory, Economic Singularity, Wealth Concentration, Automation and Productivity, Intelligence, Capital

Introduction

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is likely to emerge within the next few decades, potentially far sooner, creating systems capable of human-level reasoning, learning, and decision-making across domains. Such capabilities would transform economic and political structures by introducing a scalable, low-cost form of cognitive labour. Yet current institutions, labour markets, and governance frameworks are built for a world in which human intelligence is the limiting factor of production, leaving societies ill-prepared for the discontinuities AGI could trigger. A growing literature analyses specific components of the AI transition. However, while existing research examines automation, productivity, and political aspects, there is limited analysis of AGIʼs system-wide impact. In particular, we lack structured analysis that explores how AGI could reshape economic foundations, political equilibria, and global stability under real-world constraints. This paper addresses this gap by studying foundational technical, political and economical impacts that shape post-AGI trajectories. We aim to address where existing institutions fall short, where risks concentrate, and which policy architectures may be required to steer the transition away from collapse and toward potentially brighter futures.

Development Pathways to AGI

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) denotes an artificial system exhibiting cognitive versatility and proficiency across domains comparable to, or surpassing, that of a well-educated human adult (Hendrycks et al., 2025). Unlike narrow AI, domain-specific machine-learning systems, AGI can autonomously generalise, reason, and adapt to novel tasks. These capabilities would thus make machine intelligence functionally equivalent or higher-performing than human cognitive labour. Consequentially, AGI can be defined as “highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable workˮ (OpenAI, 2018). In this report, we will follow the formal definitions of AGI advanced by Hendrycks et al. (2025) and OpenAI (2018), delimiting the concept to realised and operational form, as opposed to aspirational or rhetorical uses. We will assume three constitutional conditions: first, that such systems exist at parity with human intelligence, in the general case and in all major aspects of intelligence; second, that they are operationally available and readily deployable by those with access to them, reflecting a level of maturity comparable to other general-purpose technologies; and third, that they are economically viable, implying that cognitive output produced by AGI is cost-competitive with, or cheaper than, equivalent human labour at scale.

AGI thus constitutes a transformational general-purpose technology: a foundational system that integrates into and reconfigures most productive, cognitive, and institutional processes. Like electricity or computation, its significance lies in pervasiveness, its capacity to alter the structure and logic of subsequent technologies, social, political and economical arrangements, as its capabilities increase. AGI naturally progresses through continuous refinement, yet its trajectory can be delineated by a series of inflection points (Table I), each unlocking qualitatively distinct forms of capability and economic control (Morris et al., 2025). Each transition redefines the economic landscape: first automating menial labour, then strategic reasoning, and ultimately autonomously undertaking the process of scientific and technological discovery. Each transition corresponds to a point where compute, energy, and data efficiency reach sufficient scale to offset prior diminishing returns. These thresholds define the material boundaries of progress in artificial intelligence. From the stage of weak AGI onward, we anticipate systems to exhibit self-improving capabilities, assisting human researchers, as shown by Wang et al. (2023). Additionally, with strong AGI, a substantial share of design and optimisation originates from the systems themselves; and by the level of a fully functioning innovating AGI, the process of advancement becomes fully endogenous, unfolding at a rate and complexity beyond direct human oversight.

This transition from execution to innovation marks a significant discontinuity in the development of artificial intelligence. It is the point where progress becomes self-reinforcing, as systems begin to generate not only economically viable output but the very methods to improve their own capabilities, triggering the potential for transformational year-on-year compounding growth in capability and productivity, as presented by The Economist (2025). This stage is captured by an A-Student Paradox: the observation that systems optimised for perfect performance within existing knowledge may initially struggle to produce new ideas, while those with greater variability or creativity advance innovation, but may provide lower initial productivity or economic returns. Both forms hold substantial economic value, the former maximising efficiency and reliability, the latter driving discovery and frontier expansion. At the point where these capacities converge, intelligence attains the characteristics of capital:

reproducible, scalable, and indefinitely generative. This threshold defines the onset of a complete post-AGI economy, in which machine intelligence itself functions as the decisive factor of production.

Table I. Levels of AGI

| Level | Definition | Capabilities |

| Narrow AI | Systems designed and trained for a single or limited set of tasks, without general reasoning or cross-domain transfer. | Performs specific functions (e.g., image recognition, translation, driving, chess) at or above human level in those tasks but fails outside its training scope. |

| General Purpose AI (GPAI) | Broadly useful AI models deployable across multiple economic sectors, e.g. through fine-tuning or prompting, yet still lacking self-directed reasoning. | Can handle varied domains with adaptation (e.g., code, text, design, analysis) but depends on human guidance and lacks unified world-model understanding. |

| Weak AGI | Artificial system achieving humanlevel performance across most cognitive domains, with general reasoning and learning ability comparable to an educated adult. | Understands instructions in any field, plans, reasons, and learns new tasksautonomously, though slower or less creative than top human experts. |

| Strong AGI | Fully human-equivalent general intelligence matching or exceeding an expert human in reasoning, learning speed, and creativity across all domains. | Performs any intellectual task an expert human can in their respective field, from office work to executive strategy and long-term planning, with comparable situational modelling and adaptability. |

| Innovator AGI | AGI capable of independently advancing science, technology, and culture, able to invent novel theories and thus fundamentally improve its own architectures. | Generates new scientific knowledge, discovers algorithms, designs machines, and iteratively improves itself or its descendants without human supervision. |

| ASI (ArtificialSuperintelligence) | Intelligence surpassing the best collective human minds in all domains, operating at vastly greater speed, scale, and strategic foresight. Approaching computational optimality in all/most situations and eventually optimal systems (Hutter, 2000) | Rapidly self-improves, manipulates or coordinates complex and abstract systems, far beyond human control. |

The Economic Singularity

Itʼs likely that AGI will eventually help us solve the central economic problem of scarcity, with transformative innovation in nuclear fusion and a distribution system that optimises upon our current markets, allowing us to maximise our use of the Earthʼs resources. However, an initial stage would see AGI entering, navigating and influencing our current scarce economy. This would trigger an initial economic shock, where policy and social direction will determine whether we reach a potential beyond our current economy. Hence, we zoom in on the problem of a post-AGI economy, from a labour market oriented lens, rather than one of post-scarcity. Economically, AGI presents not just the next innovative leap, but a complete upheaval of the current factors of production. As such, the economic system based on the current factors of production of land, labour, capital, and enterprise would be nearing its end. The Industrial Revolution shifted the order of importance between these factors of production. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, land was the most important factor, which resulted in feudal economies. After, it was capital, leading us to the modern economic system. However, AGI promises something entirely different. Economists like Daron Acemoglu have demonstrated that automation so far has shifted the tasks humans perform, rather than replacing them (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2019). AGI could be the first to break that balance. If we assume a model in which there is widespread adoption of AI agents through the labour market, we will see a gradual shift towards the eradication of labour as a factor of production. Humans will compete against these agents for employment. The agents will be cheaper to run, able to work without breaks or a need for supervision, and in many areas will be much more skilled. The forthcoming dynamic can be explained by a Stackelberg game in the labour market, where firms who own AGI can set their prices first, with the workers attempting to match it with their wages. A critical choice in modelling this game, is whether human labour and AI are modelled as complements or substitutes (Korinek and Stiglitz, 2018). If we continue our assumption that AI is a substitute for labour, this gives monopolistic power to tech firms, who in theory could set intelligence prices at a loss to undercut the cost of human intelligence. Over time the lack of employment could lead to widespread hysteresis in the labour market, creating a monopoly over whitecollar labour, or more simply: an economic singularity. We are already witnessing this without AGI, where many firms have frozen hiring and monthly layoffs are at levels unseen since October 2003 (Blumenfeld, 2025).

Many people will find it difficult to imagine an economy without labour, however it will be helpful to look at other factors of production to visualise such potential future. Under this new system, land and capital will remain as the restrictive factors, where efficiencies will continue to be found (Dehouche, 2025). The attention will be on enterprise, or in simpler terms the ability of both humans (and now AI) to generate novel ideas and economic value. The renewed focus on enterprise will be the catalyst for growing inequalities. The economic logic is as follows: if intelligence can be commoditised, and enterprise is the one factor of production that allows economic agents (whether private individuals or corporations), to gain more wealth, whoever can afford more intelligence will get richer. Under our new system outlined above, the ability of individuals to realise their enterprise will be directly correlated with how much intelligence they are able to acquire. Thus, we are likely to see an acceleration in the shift of wealth and income from the “poorerˮ majority in society to the richest. In this economy, the majority will provide the data for training these AI agents at minimal or zero cost, until eventually AI begins training and improving on its own data. From this exchange, without checks and balances in place, only the owners of AGI will benefit. This trend will continue until the wealth distribution is so starkly unequal, that there are only incentives for trade in a circle of the richest in society, eventually freezing, reducing or autocratically controlling the living standard and autonomy of the majority of the people.

This demonstrates the potential for AGI to create a closed-loop economy between the ultra-wealthy. The majority would then be in a state of subsistence or worse, marking a return to pre-Industrial Revolution economics. This dynamic has already been replicated in the investment economy, with Boyle (2025) highlighting the circular nature of investments between AI-related tech firms, and Mataloni (2025) showing that 92% of US GDP growth in the last quarter being tied to AI investments. Taken together, the evidence is consistent with two dynamics: AI attracts a disproportionate share of resources, enriching AI firms, and a K-shaped economy emerges, with living standards pulling apart. The earliest impacted economies are poised to shape the trajectory of developments through their political leverage. Over the next decade, regulation, politics, and international cooperation will be a core deciding factors for the economic outcome of AGI.

AGI as a Source of Geopolitical Power

Once intelligence becomes a scalable, tradeable, and potentially monopolised asset, the global distribution of power is inevitably redrawn. Those who master AGI first will command the defining resource of the 21st century: scalable intelligence. This reality exposes a profound global digital gap: a divide not only in access to technology, but in access to sovereignty itself. According to PwCʼs projections, North America and China will together capture nearly 70% of the global economic gains from AI by 2030, while developing countries lag behind (PwC, 2018). The implications are existential: as wealth, innovation, and computational capacity centralise in a handful of countries, the rest of the world risks becoming dependent clients in a system where control over intelligence is the ultimate determinant of autonomy. The most profound consequence of AGI lies in the geography of power. Influence will derive less from land or capital than from control over computational resources, data, and the algorithms that leverage them. Those who command the largest networks and most advanced models will dominate the cognitive infrastructure of the global economy, creating a self-reinforcing cycle: greater access to data enhances AI capability, which in turn attracts further resources and consolidates advantage. This can be further reinforced by strategic delegation: as AGI capabilities improve we could see society wide and political delegation to AI in strategic reasoning and planning. This dynamic risks producing a technological core that dictates economic and political outcomes, leaving the majority of states and populations at the periphery. Without deliberate efforts to broaden access to compute, data, and AI governance, AGI will entrench a new form of stratification. Regions lacking advanced systems may be relegated to supplying raw data or low-value labour in exchange for digital services, locking them into a subordinate position.

Since 2017, more than seventy countries have unveiled national AI strategies, each aiming to secure a position at the forefront of technological innovation (Maslej et al., 2025). While the United States continues to lead globally, China has made rapid strides across critical AI-adjacent domains, signaling its intent to reshape the future balance of power. By closely aligning with its top private AI firms, China is embedding artificial intelligence across domestic governance, economic planning, and military modernization. AI is therefore no longer just a sector of technological progress, it has become a structural factor that reconfigures capabilities and, consequently, the balance of power between the worldʼs two most consequential actors. Chinaʼs New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan (Webster et al 2017), which aims for global AI leadership by 2030 supported by a robust domestic industry, demonstrates a deliberate strategy to strengthen its technological foundation in ways that exacerbate power-transition dynamics. This trajectory highlights a structural tension in which the rise of a technologically empowered challenger steadily undermines the strategic primacy of the incumbent (the United States), dynamics that drive states into a Thucydides Trap, making great-power conflict progressively more probable. Chinaʼs AI strategy, therefore, functions not merely as a tool of development but as a mechanism of internal balancing aimed at narrowing the power differential with the United States, thereby unsettling longstanding hierarchies within the international system. As both states interpret each other’s technological advances as indicative of future strategic intentions, the risk is that the pursuit of superiority in AI intensifies perceptions of threat, heightens mistrust, hence triggering a security dilemma that pushes the system toward a more volatile equilibrium in which miscalculation becomes more likely (Allison, 2017). In the anarchic international system, where states are locked in perpetual competition for power, AGI will emerge as the ultimate instrument of advantage, granting its possessor unparalleled command over information, strategy, and decision-making, rendering the strategic influence of nuclear weapons almost obsolete. This is because AI can transform the strategic environment into a “deception-dominantˮ landscape, where states can obscure capabilities and conventional assumptions about offense‑defense balances no longer hold (Geist, 2023).

While some have proposed governance mechanisms such as a non-proliferation plus norms-of-use regime for AI or a United Nations supported International Artificial Intelligence Agency (IAIA), the feasibility of these frameworks is constrained by asymmetric technological capabilities, competing national interests, and lack of transparency (Novelli et al., 2024). In the future, AI governance is likely to adopt a hybrid model, combining multilateral oversight, national regulation, and private-sector accountability, because no single actor or institution can effectively manage the global, dual-use, and rapidly evolving nature of AGI. Its primary role will be risk mitigation, focusing on preventing catastrophic outcomes, rather than guaranteeing equitable access or fully constraining strategic competition, because the competitive and anarchic nature of the international system makes equal distribution and complete restraint unrealistic.

Conclusion

AGI represents the moment when intelligence becomes reproducible capital. As that shift unfolds, traditional labour market dynamics weaken and the distribution of economic value detaches from human participation. The resulting concentration of productive power risks a historic reversion: a narrow class controlling the engines of wealth creation while the majority are economically marginalised. The pathways are not predetermined. Public policy, corporate governance and global regulation could shape markets. Yet there is no guarantee that such measures will arise or be effective without coordinated recognition of the stakes. Economic transformation therefore becomes a test of institutional adaptability and social will. What begins as an economic disruption may soon confront the deeper question of who commands power in a world shaped by intelligent systems. The answer to that question leads naturally into broader political concerns that cannot be ignored for long.

Bibliography

Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2019). Automation and New Tasks: How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(2), 3-30. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.2.3

Allison, G. (2017). Destined for war: Can America and China escape Thucydidesʼs trap? Graham Allison. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017, 384 pp. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 51(3), 705- 706. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423917001433

Blumenfeld, C. M. (2025, November 6). October Challenger Report: 153,074 Job Cuts on Cost-Cutting & AI. Challenger, Gray & Christmas, Inc. | Outplacement & Career Transitioning Services. https://www.challengergray.com/wpcontent/uploads/2025/11/Challenger-Report-October-2025.pdf

Dehouche, N. (2025). Post-Labor Economics: A Systematic Review. Preprints.org. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202504.0444.v3

Geist, Edward, ‘Strategic Stability in a Deception-Dominant World’, Deterrence under Uncertainty: Artificial Intelligence and Nuclear Warfare (Oxford, 2023; online edn, Oxford Academic, 28 Sept. 2023), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192886323.003.0007

Hendrycks, D., Song, D., Szegedy, C., Lee, H., Gal, Y., Brynjolfsson, E., Li, S., Zou, A., Levine, L., Han, B., Fu, J., Liu, Z., Shin, J., Lee, K., Mazeika, M., Phan, L., Ingebretsen, G., Khoja, A., Salaudeen, O., Hein, M., Zhao, K., Pan, A., Duvenaud, D., Li, B., Omohundro, S., Alfour, G., Tegmark, M., McGrew, K., Marcus, G., Tallinn, J., Schmidt, E., & Bengio, Y. (2025). A definition of AGI. arXiv.

Hutter, M. (2000). A theory of universal artificial intelligence based on algorithmic complexity. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/cs/0004001

Korinek, A., & Stiglitz, J. E. (2018). Artificial intelligence and its implications for income distribution and unemployment. In A. Agrawal, J. Gans, & A. Goldfarb (Eds.), The economics of artificial intelligence: An agenda (pp. 349-390).

National Bureau of Economic Research. https://ideas.repec.org/h/nbr/nberch/14018.html

Maslej, N., Fattorini, L., Perrault, R., Gil, Y., Parli, V., Kariuki, N., Capstick, E., Reuel, A., Brynjolfsson, E., Etchemendy, J., Ligett, K., Lyons, T., Manyika, J., Niebles, J. C., Shoham, Y., Wald, R., Walsh, T., Hamrah, A., Santarlasci, L., Lotufo, J. B., Rome, A., Shi, A., & Oak, S. (2025). Artificial intelligence index report 2025. AI Index Steering Committee, Institute for Human-Centered AI. Stanford University. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.07139

Mataloni, L., OʼConnell, C. , & Pinard, K. (2025, September 25). Gross Domestic Product 2nd Quarter 2025 (Third Estimate), GDP by Industry, Corporate Profits (Revised), and Annual Update [Review of Gross Domestic Product 2nd Quarter 2025 (Third Estimate), GDP by Industry, Corporate Profits (Revised), and Annual Update]. BEA; Bureau of Economic Analysis. https://www.bea.gov/sites/default/files/202509/gdp2q25-3rd.pdf

Morris, M. R., Sohl-dickstein, J., Fiedel, N., Warkentin, T., Dafoe, A., Faust, A., Farabet, C., & Legg, S. (2023, November 4). Levels of AGI: Operationalizing Progress on the Path to AGI. ArXiv.org.https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2311.02462

Novelli, C., Hacker, P., Morley, J., Trondal, J., & Floridi, L. (2024). A robust governance for the AI Act: AI Office, AI Board, Scientific Panel, and national authorities. European Journal of Risk Regulation. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2024.57

OpenAI. (2018). OpenAI Charter. https://openai.com/charter

PwC. (2017). Sizing the prize: PwCʼs global AI study Exploiting the AI revolution. PwC. https://www.pwc.ch/en/publications/2017/pwc_global_ai_study_2017_en.pdf

The 2025 AI Index Report. Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI). Available at: https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2025-ai-indexreport

The Economist. (2025, July 24). The economics of superintelligence. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2025/07/24/the-economics-ofsuperintelligence

The Economist. (2025, July 24). What if AI made the worldʼs economic growth explode? The Economist. https://www.economist.com/briefing/2025/07/24/what-if-ai-made-the-worldseconomic-growth-explode

Wang, H., Fu, T., Du, Y., Gao, W., Huang, K., Liu, Z., Chandak, P., Liu, S., Van Katwyk, P., Deac, A., Anandkumar, A., Bergen, K., Gomes, C. P., Ho, S., Kohli, P., Lasenby, J., Leskovec, J., Liu, T. Y., Manrai, A., Marks, D., Ramsundar, B., Song, L., Sun, J., Tang, J., Veličković, P., Welling, M., Zhang, L., Coley, C. W., Bengio, Y., & Zitnik, M. (2023). Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature, 620(7972), 47-60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586023062212

Webster, G., Creemers, R., Triolo, P., & Kania, E. (2017). Full translation: Chinaʼs “New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Planˮ (2017). New America. https://www.newamerica.org/cybersecurity-

initiative/digichina/blog/full-translation-chinas-new-generation-artificialintelligence-development-plan-2017/

Supplementary Literature

Articles and Studies https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/speculative-timeline-agi-from-job-zappingbots-utopia-luis-caldeira-qezaf/ https://www.resilience.org/stories/20250612/ai-utopia-ai-apocalypse-and-aireality/

https://www.dallasfed.org/research/economics/2025/0624 https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/15/opinion/artifical-intelligence-2027.html https://arxiv.org/html/2502.07050v1 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10438599.2020.1839173https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/magazines/panache/ex-googleexecutive-mo-gawdat-predicts-a-dystopian-job-apocalypse-by-2027-ai-willbe-better-than-humans-at-everything-even-ceos/articleshow/123123024.cms? from=mdr https://venturebeat.com/ai/hugging-face-co-founder-thomas-wolf-justchallenged-anthropic-ceos-vision-for-ais-future-and-the-130-billion-industry-istaking-notice https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/474267/if-anyone-builds-it-everyone-diesby-soares-eliezer-yudkowsky-and-nate/9781847928924 https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.02462 https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202504.0444#sec3-preprints-160890 https://www.amazon.co.uk/Superintelligence-Dangers-Strategies-NickBostrom/dp/0199678111 https://medium.com/intuitionmachine/the-economy-after-intelligenceebf1f1757f66 https://www.forwardfuture.ai/p/scale-is-all-you-need-part-42-the-post-agiworld https://genesishumanexperience.com/2025/09/18/the-imminent-demise-ofcapitalism-navigating-a-frictionless-path-to-post-agi-economics/ https://medium.com/human-spaces/the-post-agi-economy-a-future-focusedon-human-connections-and-happiness-ee5468a5b652 https://garymarcus.substack.com/p/the-ai-2027-scenario-how-realistic https://corneliamagazine.com/article-set/utopia-vs-the-apocalypse https://www.economist.com/briefing/2025/07/24/what-if-ai-made-the-worldseconomic-growth-explode

Videos https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XySs_KgzyDchttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fwD9EnCzujM https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XTQ2ii-k2sw&t=452s https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NbL7yZCF6Qhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xl0xgXejAa8 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e1Hf-o1SzL4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-zF1mkBpyf4https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D8RtMHuFsUw https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q0TpWitfxPk https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KzUxJi_5gGIhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tUqYIQ1hzUA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oLDcbkEqi-M https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T2OHjHPkUzM