How did the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent austerity measures impact housing markets and spatial inequality in Greece?

The 2008 financial crisis triggered severe economic upheaval worldwide, and Greece became one of the hardest-hit countries in its aftermath. This banking crisis, which had its effects felt all over the world, quickly transformed into an economic and debt crisis for Greece. By 2009, it was clear that the Greek government had been borrowing excessively and hiding the true size of its debts (European Commission, 2010). As a result, many investors lost trust in the Greek economy, and the country was forced to accept a financial bailout from the EU and IMF in return for strict economic changes, known as austerity measures.

This essay focuses on two important effects of the crisis in Greece. Firstly, it focuses on the changes in the Greek housing market. When referring to the housing market, I mean house prices, construction, and the ability of people to buy or rent homes. Secondly, it focuses on the rising spatial inequality within the country: by this, I refer to the disparities between wealth and opportunities across different geographical spaces, such as rich and poor areas, or cities and rural regions. What is useful, is that spatial inequality allows us to specify our focus, even to neighborhoods within cities, by looking at the differences between the more and less advantaged ones.

Background: Greece’s Crisis and Austerity Measures

Greece had underlying economic vulnerabilities before the 2008 financial crisis that led to the consequences being even more profound than in other countries. The country had accumulated high public debt (well over 100% of GDP) and was engaging in large annual budget deficits[1]. After joining the eurozone in 2001, Greece began borrowing heavily and increasing its public expenditures. However, its fiscal management was weak. By 2009, it emerged that Greece’s deficit was far higher than reported—over 15% of GDP—undermining investors’ confidence (Smith, 2017).

After the crisis hit, tax revenues significantly fell, which made Greece’s debt burden even worse. Furthermore, investors demanded higher interest rates on Greek bonds, causing Greece to enter a sovereign debt crisis by late 2009.

The crisis forced Greece to seek emergency loans from the EU and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Hence, in 2010, 2012, and 2015, Greece entered “bailout agreements” that provided them with financial support. However, this support came with a cost; the EU and IMF made Greece implement strict austerity policies which were supposed to ensure their ability to pay them back. The government drastically cut public spending, including reductions in public-sector salaries and hiring freezes. Additionally, arguably the worst aspect of the austerity measures was the cut to citizens’ pensions, due to the fact that many households, particularly in Greece, depended on the pensions system as a safety net. Simultaneously, taxes were increased as well. Value Added Tax (VAT) on goods and services across the country was raised, income tax thresholds were lowered to increase the amount of taxpayers, and new taxes were introduced—such as ENFIA. ENFIA is particularly important for this essay because this was a nationwide property tax implemented in 2014, which forced all property owners to pay an annual levy (Radin, 2024). The government, wanting to raise their revenues and improve efficiency, also decided to privatize state assets by selling stakes in everything from utilities to ports and airports.

Following the implementation of these policies, public budgets and urban investments endured a complete transformation. For instance, during the first years of the crisis, public development was “dramatically reduced,” especially hurting the construction industry (Chatzitsolis, 2014). Local governments, which were reliant on central funding, were unable to fund and maintain public services as well, such as city parks and cleaning services. The combination of the ongoing recession, coupled with the austerity measures, led to an economic contraction in Greece of about 25% of GDP over the time period between 2008-2015 (OECD, 2016). Unemployment rose from around 8% in 2008 to a peak of over 27% by 2013 (Andriopoulou, 2020), and the youthful portion of the population faced unemployment rates above 50%. This context—a depressed economy, drastically reduced public spending, and higher taxes—set the stage for a collapse in the housing market and gave rise to new forms of spatial inequality, which I will explore next.

Housing Market during and after the Crisis

Greece’s housing market suffered heavily as a result of the crisis and austerity measures. During the “boom” of the early 2000s, consumer confidence had fueled a surge in housing transactions and construction. This trend, however, quickly stopped in 2008. Property values began to fall steadily as the years passed, showing how both the general economic depression and specific policies (like new taxes) were hindering real estate demand among the Greek population.

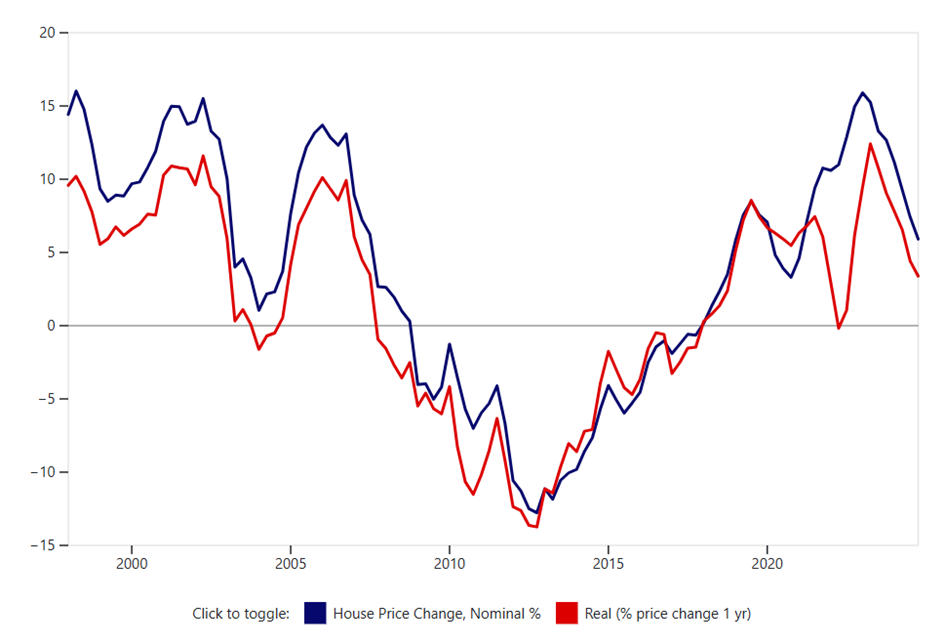

Figure 1: Greece’s House Price, Annual Change, Source: (Bank of Greece)

In Figure 1, we see the magnitude of the housing crash in Greece. Between 2007 and 2017, the index of residential property prices in urban areas dropped by approximately 42% of its value (Delmendo, 2025). In other words, a home that might have sold for €200,000 at the peak would only have been worth around €115,000 ten years later. By 2013, the property market was arguably already frozen due to the lack of transactions happening, as buyers were scarce and many sellers were unwilling or unable to sell at such low prices.

Greek families traditionally view real estate as a safe investment (“every family must own two or three properties” is a common norm), making the effect of this crisis even worse. Although the decline affected all types of housing and all regions around the country, urban centers such as Athens and Thessaloniki were hit particularly hard. By one estimate, Athens’s apartment values fell about 44% from their pre-crisis peak to the trough around 2017 (Bank of Greece, 2018). Smaller cities and rural areas experienced major drops too, though somewhat less significant (around 30-40% declines) (Bank of Greece, 2018). Such a steep nationwide fall in house prices meant that a lot of newer home buyers in Greece were now completely “underwater” on their mortgages—owing more to the bank than their home was now worth.

Several factors fuelled this collapse. Firstly, incomes and employment dropped significantly due to the recession and austerity policies (public-sector pay cuts, private-sector layoffs, etc.), meaning that Greek people simply didn’t have the financial means to afford housing. Secondly, credit availability also experienced a major decline: Greek banks, burdened by non-performing loans, virtually stopped issuing new mortgages (OECD, 2016). Thirdly, the introduction of the ENFIA property tax made owning property in Greece much more costly. The ENFIA property tax began, in 2011, as an emergency levy and then became permanent in 2014 (Radin, 2024). As a result, even empty or inherited houses carried a yearly tax bill, forcing some owners to sell properties they could no longer afford to keep. The overall tax burden on property owners in Greece roughly doubled from pre-crisis times, when considering ENFIA alongside increased VAT and income taxes on imputed rent (Chatzitsolis, 2014). Greeks fell behind on mortgage payments or property-related debts. By 2016, nearly half of all loans in Greece’s banking system were non-performing—a significant portion of these were mortgages (Bensasson, 2023).

As mentioned before, the peak of the crisis in Greece (around 2013-2015) saw the housing market essentially frozen. Transactions were extremely scarce—annual real estate sales dropped from over 74,000 in 2009 to barely 24,000 in 2013, reflecting an almost stagnant market (Chatzitsolis, 2014). The people who weren’t in desperate need to sell their properties generally held off, while buyers waited as they were anticipating prices to drop even further. Notably, many young adults, unable to afford rent anymore, moved back in with their parents, and extended families consolidated into single households to save on housing costs[2]. However, this familial safety net couldn’t completely prevent a significant increase in homelessness, particularly in major cities such as Athens, where estimates from 2015 state 15,000 people were homeless in greater Athens, much higher than pre-crisis numbers (Andriopoulou, 2020).

From 2017 onwards, the housing market began to gradually recover once more. Several factors contributed to this recovery: firstly, Greece’s economy started growing again (after 2016), restoring some domestic confidence. Secondly, foreign investors and buyers began to see Greek real estate as a bargain (European Commission, 2010). By 2018, Greece had introduced incentives like the “Golden Visa” program, offering residency permits to non-EU citizens investing at least €250,000 in property. This attracted significant interest from China, Russia, and the Middle East. Foreign direct investment in Greek real estate hit a record €2 billion in 2018, helping to stop the decline in property prices (Bensasson, 2023). Thirdly, a tourism boom and the rise of rental platforms such as Airbnb also increased demand for property in various locations around Greece. Specifically in Athens and popular islands, investors bought apartments and houses to convert them into holiday rentals, significantly increasing property values in those areas (Georgiopoulos, 2022). By the third quarter of 2022, nationwide house prices were rising at an 11% year-on-year pace, led by a 13% surge in Athens (Georgiopoulos, 2022).

This recovery, however, has been uneven. Clearly, the areas and regions that have been able to bounce back most effectively from the crisis are the major cities (Athens and Thessaloniki) and the popular tourist islands such as Mykonos and Santorini—who have all seen double-digit annual price growth (NTL Corporate Services, 2024). In contrast, many rural towns and poorer city suburbs have only benefitted at a fraction of what other areas have, if at all. As of 2022, Greece’s national house price index was still roughly 25% below its 2008 peak in real terms, despite recent gains (Georgiopoulos, 2022). Thus, while the Greek housing market crisis may have ended, the recovery differed across various geographical regions of the country—seeing a dynamic rebound in areas with external demand and economic activity, versus a slower response in less advantaged areas. These patterns connect closely to the issue of spatial inequality, as discussed next.

Spatial Inequality in Greek Cities

Before the crisis, Greek cities showed moderate levels of spatial inequality in relation to international standards. In Athens, for instance, working and middle-class households were often intermingled across neighbourhoods, and even immigrant communities—who arrived mainly in the 1990s-2000s—tended to settle equally in central areas, reducing any real visible segregation (Maloutas, 2014). At the regional level, Athens and a few other areas proved relatively more resilient after the crisis, while poorer regions suffered more dramatic setbacks (Maloutas, 2014). Many smaller cities (like Larissa, Patras, Kavala) experienced what scholars in urbanisation call “shrinkage”: the closing of local industries, the emigration of young people to Athens or abroad, and the abandonment of city centres, leaving stores vacant and buildings abandoned (Manika, 2020). A study of Larissa—a medium-sized city—found a sharp rise in commercial vacancies on once busy streets during the crisis years, something that could also be seen in many other similar provincial towns across the country. This dynamic—characterized by a concentration of growth in the central regions and major cities like Athens—has further accentuated spatial imbalance, as more peripheral regions become even more abandoned.

Within Athens in particular, the crisis’s spatial impact had been felt too. In central Athens, the early crisis years saw a visible decline in some neighbourhoods. Areas in the downtown core (e.g., around Omonia Square, parts of Exarchia and Patision Street) experienced shop/business closures, rising crime rates, and a surge in vandalism and graffiti in the streets. This links back to the combination of both austerity (cuts in municipal services, policing, maintenance) and the recession (reducing foot traffic and investment), which led to a number of previously vibrant locations becoming marked by empty shops (Manika, 2020). Conversely, upper-class suburbs in North Athens (like Filothei and Ekali) were much less affected compared to other areas. However, even wealthier households faced strains such as higher property taxes on luxury homes and difficulties accessing bank credit (Manika, 2020). The working-class suburbs of West Athens (Egaleo, Perama, Menidi) experienced this crisis in a completely different way as well. Unemployment increased significantly as industrial jobs were vanishing. These areas saw rising poverty rates and reliance on soup kitchens or local charity networks during the worst years of the recession[3].

By the late 2010s, spatial inequalities in Athens were manifesting in new ways. As the economy stabilized once again, certain neighbourhoods—especially those attractive to tourists or foreign investors—began to gentrify and recover, while others lagged behind. For example, central districts like Koukaki and Kerameikos saw an influx of Airbnb-oriented investment, renovating properties and increasing the amount of rent (NTL Corporate Services, 2024). Meanwhile, some low-income areas like those discussed before in West Athens experienced little new investment and saw continued high vacancies in commercial properties. This reflects a largely uneven recovery, contributing to more urban spatial inequality. Parts of the inner city transformed into tourist hotspots, whereas poorer peripheral districts remained trapped in crisis-era stagnation.

Linking Housing and Spatial Inequality: Causes and Consequences

The housing crash and the rise in spatial inequality during Greece’s crisis were deeply interwoven. It is important to bring both phenomena together and analyse them in a way that shows how each went on to reinforce the other to create a vicious cycle for Greece.

Firstly, housing is a major component of household wealth in Greece, so the steep drop in home values translated into a substantial loss of wealth for Greek families overall. Middle-class households saw their net worth decrease as property prices decreased as well, which also meant that they weren’t able to sell property to cushion income losses anymore. In turn, this led to a general deterioration of living standards in Greece, which was reflected in relatively stable Gini inequality measures, meaning that the crisis was distributed equally amongst the population (Danchev & Giakas, 2024).

Secondly, as incomes fell and taxes rose, housing became harder to afford. By the early 2020s, Greek households were spending over 32% of their income on housing-related costs—the highest in the EU (Danchev & Giakas, 2024). People who were hit particularly hard were renters and mortgage holders. Many families coped by organizing shared homes, moving in with relatives, or relocating to cheaper neighborhoods. In Athens, this changed the social makeup of inner-city districts. Some low-income renters were pushed out as rents stayed high relative to incomes, leading them to move to already poor areas. Meanwhile, residents who had more financial freedom were better off as they stayed in desirable areas, some even buying homes at low prices during the downturn. Over time, this contributed to wealth becoming more spatially unequal.

Thirdly, neighborhood decline and urban disinvestment was also a consequence, as discussed before. In some areas, the housing market collapse led to long-term neglect. When buildings turned vacant, owners and local governments lacked the necessary funds to help maintain them. This was clear in Athens, where some neighborhoods became full of empty shops and vandalized buildings (Manika, 2020). Poorer areas, like before, saw the worst effects. Residents who could afford to move left, while crime and poverty increased. Schools and services also declined, further damaging opportunities for local children and families. Because of budget cuts, local authorities couldn’t do much to help. These areas were stuck in poverty traps.

Lastly, another reason the housing crisis was so impactful is that Greece had very little public housing. Unlike many European countries, it had no large-scale social housing system to help struggling families during the crisis. Until 2017, there were no national minimum income programs, further intensifying the hardship of the country (OECD, 2016). This meant that people who didn’t have strong family ties—such as migrants or single adults in cities—faced the greatest risk of homelessness. While many Greeks moved in with relatives, others ended up on the streets. The housing crisis, combined with limited government support, made it harder for poor communities to escape poverty.

Together, these four factors show how housing and inequality reinforced one another, creating a downward spiral that made it hard for Greece to recover. Poorer neighbourhoods declined faster and struggled to recover, while wealthier groups were able to buy cheap homes and benefit from the rebound. The crisis changed not only the economy, but also the physical and social layout of Greek cities.

Evaluation: Recovery and what we have Learned

After nearly a decade of hardship, Greece began to recover in the late 2010s. Still, the recovery has been slow and uneven as we have seen throughout the essay.

Family support and community resilience: One reason Greece avoided an even deeper social crisis was the strength of family and community networks. Many people survived because they could live with relatives or receive help from parents and grandparents. Local communities also organized support networks—like food banks or time banks—to help each other[4]. However, relying on family has its limits. Savings ran out, older people’s pensions became overburdened, and people without family support—especially in cities—were at high risk of homelessness or extreme poverty. The crisis showed that Greece’s formal safety nets were too weak.

Policy changes and social protection: Since 2017, Greece has introduced a minimum guaranteed income and discussed housing reforms. These steps are important to avoid similar problems in future crises. Affordable housing programs, rent subsidies, and urban renewal projects were considered, especially in areas hit hard by poverty or abandonment. Another key lesson is the importance of balanced fiscal policy. Many experts, including the IMF, have admitted that the early austerity measures in Greece were too harsh and caused deeper recession than expected (IMF, 2013). Budget cuts harmed the economy by reducing demand, destroying jobs, and eroding social cohesion. For future crises, governments should avoid cutting too deep, too fast. Protecting key public services—like schools, housing, and infrastructure—can help maintain long-term economic potential. In Greece’s case, some of the spending cuts targeted exactly these areas, worsening inequality and delaying recovery.

Investing in places left behind: Another major takeaway is that economic recovery does not reach everyone equally. In Greece, cities like Athens recovered faster than small towns or rural regions. Within cities, richer areas bounced back sooner, while poorer districts remained neglected. To fix this, targeted investment is needed. For example, using EU recovery funds to support regions like Western Macedonia—which was hit by coal decline—or turning abandoned buildings into student housing in central Athens, are steps in the right direction. Without such interventions, markets alone may worsen inequality—investors flock to profitable areas, while disadvantaged communities fall further behind.

Managing foreign investment: Since 2016, Greece has seen a rise in foreign buyers purchasing properties, especially through programs like the Golden Visa. This brought in needed capital and boosted construction jobs, but it also pushed up housing prices in popular areas, making it harder for locals to afford homes (Reuters, 2024). The government has responded by tightening regulations—raising the minimum investment threshold and discussing restrictions on short-term rentals. These efforts aim to balance the benefits of investment with the need to protect affordable housing for Greek residents.

Final reflections: Greece’s recovery remains incomplete, but it has shown the country’s capacity for resilience. Families, communities, and local governments did what they could to survive. But the crisis also revealed weaknesses—particularly in social policy, housing systems, and regional equity. For other countries, Greece offers a cautionary tale. Austerity without protection deepens inequality. Housing is central to both economic stability and social cohesion. And if recovery is not inclusive, it risks reproducing the very problems it seeks to fix.

Greece’s crisis serves as an important reminder that economic crises are events that have impacts in a multidimensional manner. In this case, the geographic and social dimensions of the matter are arguably just as significant as the fiscal and financial aspects. The country’s experience shows the importance of being able to adapt and mitigate the numerous consequences vulnerable populations are faced with in these times—through social protection and perhaps more gradual pacing of austerity—to prevent extreme outcomes like humanitarian crises or mass impoverishment.

It also highlights the importance of housing itself: being a victim of global shocks and a key contributor to social welfare, allowing people to keep their homes and mitigating forced displacement should be a priority in any crisis response. For Greece specifically, the crisis has taught a valuable lesson in terms of recovering from the damages in the 2010s, including rent subsidies and regional development programs. On the other hand, Greece serves as an example of the dangers of having an imbalance caused by excessive debt and fiscal mismanagement. A balanced approach is required to recover, to help restore economic resilience, social cohesion, and spatial equality. Greece’s path out of the crisis offers hope that with time and well-designed policies, any challenge—even the worst of financial crises—can be overcome and used to build economic frameworks that withstand future ones.

Works Cited

Andriopoulou, Eirini, et al. “Hellenic Observatory Discussion Papers.” LSE.ac.uk, June 2020, www.lse.ac.uk/Hellenic-Observatory/Assets/Documents/Publications/GreeSE-Papers/GreeSE-No149.pdf.

Bank of Greece. “Indices of residential property prices: Q4 2017.” Bankofgreece.gr, 15 Feb. 2018, www.bankofgreece.gr/en/news-and-media/press-office/news-list/news?announcement=3c7afb0b-fed8-4965-b2af-6a99a7058dc0.

Bensasson, Margarita. “Housing and financial stability in Greece.” Grecology.org, 17 July 2023, www.grecology.org/p/housing-and-financial-stability-in.

Chatzitsolis, Nikos. “The Boom and Bust of the Greek Housing Market.” CRE.org, 22 Apr. 2014, cre.org/real-estate-issues/boom-bust-greek-housing-market/.

Danchev, Svetoslav, and Georgios Giakas. “Equally poorer: inequality and the Greek debt crisis.” Fiscal Studies, vol. 45, no. 1, 20024, pp. 1-27.

Delmendo, Larry C. “Greece’s Residential Property Market Analysis 2025.” GlobalPropertyGuide.com, 2 July 2025, www.globalpropertyguide.com/europe/greece/price-history.

European Commission. The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece. European Commission, 2010.

Georgiopoulos, George. “Greek residential property price recovery picks up in third quarter.” Reuters, 29 Nov. 2022, www.reuters.com/markets/europe/greek-residential-property-price-recovery-picks-up-third-quarter-2022-11-29/.

“Greece to raise investment price for ‘golden visas’, PM says.” Reuters, 9 Feb. 2024, www.reuters.com/world/europe/greece-raise-investment-price-golden-visas-pm-says-2024-02-09/.

IMF. Greece: Ex Post Evaluation of Exceptional Access under the 2010 Stand-By. IMF, 20 May 2013, file:///C:/Users/Cavallaro/Downloads/002-article-A000-en.pdf.

Maloutas, Thomas. “Social and spatial impact of the crisis in Athens.” Region et Developpement, 2014.

Manika, Stavroula. “Portraying and Analysing Urban Shrinkage in Greek Cities—The Case of Larissa.” Scientific Research, vol. 10, no. 6, 2020.

NTL Corporate Services. “The Greek Housing Market: A Golden Opportunity for Investors.” NTLtrust.com, 30 Sept. 2024, ntltrust.com/news/second-residency/the-greek-housing-market-a-golden-opportunity-for-investors/.

OECD. OECD Economic Surveys Greece. OECD, 10 Mar. 2016, www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-economic-surveys-greece-2016_eco_surveys-grc-2016-en.html.

Radin, Itai. “Assessing the problem of affordable housing in Greece.” Springer Nature, 2 Dec. 2024, link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s44327-024-00037-z.

Smith, Helena. “‘Greek Activists Target Sales of Homes Seized over Bad Debts’.” The Guardian, 11 Mar. 2017, www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/11/greek-activists-target-sales-of-homes-seized-over-bad-debts.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/11/greek-activists-target-sales-of-homes-seized-over-bad-debts#:~:text=only%20a%20fraction%20of%20auctions,relaxation%20of%20laws%20protecting%20defaulters (Accessed on 07/07/2025)

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/11/greek-activists-target-sales-of-homes-seized-over-bad-debts#:~:text=only%20a%20fraction%20of%20auctions,relaxation%20of%20laws%20protecting%20defaulters (Accessed on 07/07/2025)

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/aug/02/greece-family-ties-debt-crisis#:~:text=Even%20before%20the%20crisis%2C%20Greece%27s,and%20state%20support%20are%20limited (Accessed on 11/07/2025)

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/feb/10/greek-homeless-shelters-debt-crisis?utm (Accessed: 17/07/2025)