My first two articles on the Review had to do with Europe, and the last one specifically analysed Germany’s economy. In this piece, I look at a very different country, but one which is at a more explicitly decisive point of its history.

At the time of their independence, in 1971, after a deadly war to separate from West Pakistan, Bangladesh was one of the world’s poorest countries. In its first years as an independent nation, many more people died from a famine, caused by resource mismanagement and food shortages. It would not be until the 1980s, when a series of economic reforms were carried out to modernise the economic system, that the country started to experience growth.

In addition to these reforms, the intervention of NGOs and other social institutions, such as the microfinance lender Grameen Bank, was crucial in lifting those in need out of poverty. Following this initial momentum, Bangladesh entered an industry which would prove to be crucial for its development: the Ready-Made Garment (RMG) business. Like China or Vietnam, the country saw in the textile industry a crucial element for development. In the case of Bangladesh, an entrepreneurial social class started to emerge: as the country did not have big endowments in capital, the push came from relative cheap labour as compared to abroad, and was characterised by the rise of a middle-class of self-made business owners, some of which are large industrial players nowadays. Today, clothes account for a great majority of the nation’s total exports, favoured by government initiatives like the export development fund.

Moreover, the important economic development through the second half of the 20th century also came with progress for women, who are now a considerable part of the working population, and were able to gain independence in this period of growth, although progress remains to be made in the area of equality. Part of these advancements is due to the success of microloans in the country, which targeted women from rural areas, who could not achieve economic freedom until that moment.

Some social advances where also pushed by Sheikh Hasina, daughter of the first elected president of Bangladesh. She first served as prime minister in 1996 and then in 2009, and was a pillar of Bangladeshi politics all throughout the beginning of the 21st century.

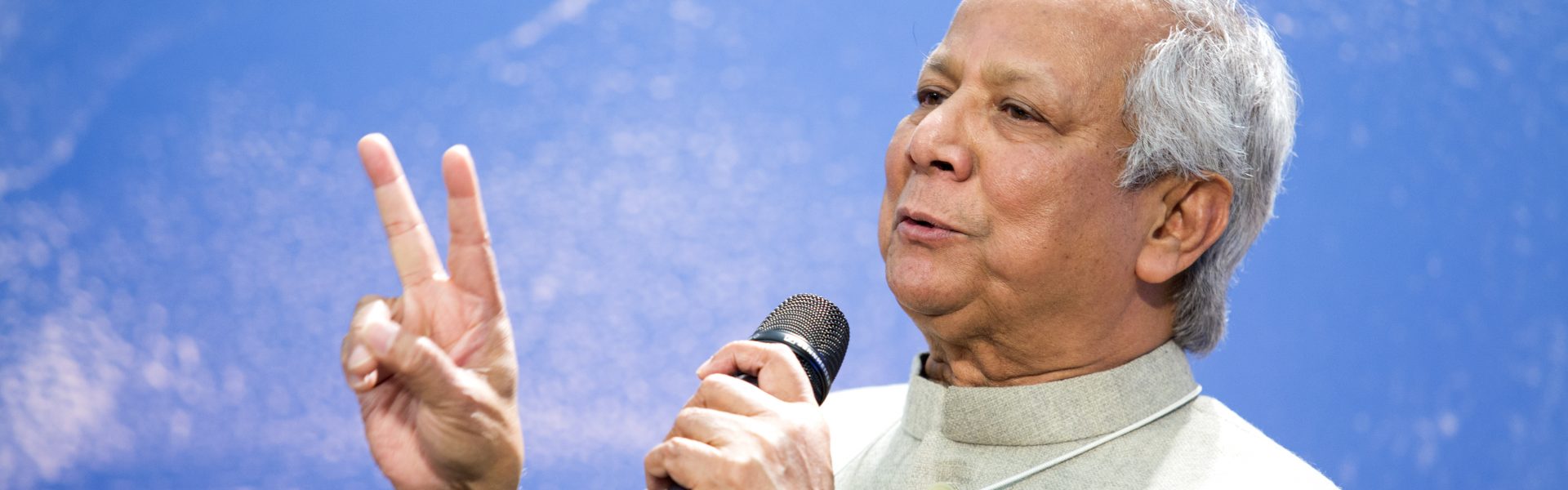

Fast forward to August 2024, and the future of Bangladesh is unclear. Muhammad Yunus, the 84-year-old Nobel Peace Prize-winning philanthropist, founder of Grameen Bank, and nicknamed the “banker of the poor” thanks to his big efforts in developing microfinance in Bangladesh, took office as caretaker of the country on August 7th.

This was after years of harsh political repression and autocratic derives from the part of the ruling party, the Awami League (AL), and its leader, the aforementioned Sheikh Hasina. Although the country did see some of the best years of economic development under its rule, the long-standing government became increasingly hostile towards opposition, reaching an extreme point of persecution of dissidents, election manipulation, and political violence, which agitated the country’s youth.

Starting as a localised movement of students against a government-imposed nepotistic quota system for accessing public roles (while Bangladesh suffers from a problem of high youth unemployment), student-led protests became increasingly mainstream as the country went through the economic effects of the pandemic, such as painful rises in (food-price) inflation, which lasted longer and reached higher than in other economies, and electricity shortages. All of this was accentuated by severe floodings in the countryside.

Therefore, escalation was inevitable. Since July 1, when students started protesting against the job quotas, the demonstrations became increasingly violent in many cases. The government started to shut down universities, cutting off the internet, and imposing curfews. Although the quota system disappeared for the most part on July 21st, it was too late by then, and on July 29th, the protesters called for Sheikh Hasina to leave the government. Finally, on August 5, the Prime Minister resigned and fled the country, as the people stormed her palace in Dhaka.

On the global sphere, the current geopolitical landscape is all but helpful for the new Bangladesh. Sheikh Hasina’s government built strong ties with India over the years, a relationship which could now be at stake. Going forward, China could acquire more protagonism in the country’s international relations, although it was already Bangladesh’s biggest trade partner. Of course, Trump’s tariffs and the global economic chaos witnessed in the last months will not help the country’s export-based textile industry.

As of March 2025, there was still no tangible consensus on what the future of the country will be. Some argue that time is needed to reform the institutions, while others demand elections urgently, the provisional government having announced its intention of holding them in late 2025 or early 2026. While this happens, the country is experiencing its worst crime wave in years, with figures for murders, muggings and robberies taking off.

Some commentators point to the difficulties of the interim government in maintaining order. While it is a big responsibility of the caretaker administration to include people from different backgrounds in order to ensure an inclusive future for the country, this can make action difficult in times when unified, strong action is needed, such as today.

Economically, while the inflation rate has been coming down since the end of 2024, it still stood at 9.35% in March 2025. Apart from this, there are many more problems going forward, some of them hidden below the surface. For example, under new Governor Ahsan Mansur, the Bangladeshi Central Bank has established 11 specialist teams to track the assets of some families that smuggled their fortunes abroad after Sheikh Hasina’s fall. This may seem anecdotic, but the quantities which the Bank is investigating are huge. Just one family, for example, is suspected of having moved $15bn, withdrawing nearly 90% of a single bank’s total deposits. This is just one instance of the level of corruption that the country must now get over.

Bangladesh stands today at a crossroads, shaped by a legacy of resilience and reinvention. From a war-torn, famine-struck nation to one of South Asia’s most dynamic economies, its progress has been hard-won, but it may not be irreversible. The current political transition, triggered by years of repression and popular unrest, reveals both the fragility and the potential of the nation’s democratic and economic institutions. Whether this moment becomes a rebirth or a relapse will depend on the ability of the interim government, and eventually its elected successor. They will have to confront entrenched corruption, protect civic freedoms, and steer a volatile economy toward sustainable growth.