Universal healthcare is something that the majority of the developed world has the ability to experience. Whether it is the UK’s NHS, Italy’s SSN or Canada’s Medicaid, residents of these countries could not be faulted if they assumed all nations with the means to administer this system had done so. And whilst each wealthy country’s strategy to deliver healthcare slightly differs, one protrudes like no other – the United States. There is no doubt that an economy quantified at almost $30 trillion this year is able to find the money to employ a state-sanctioned healthcare system to all citizens, so the question is – why not?

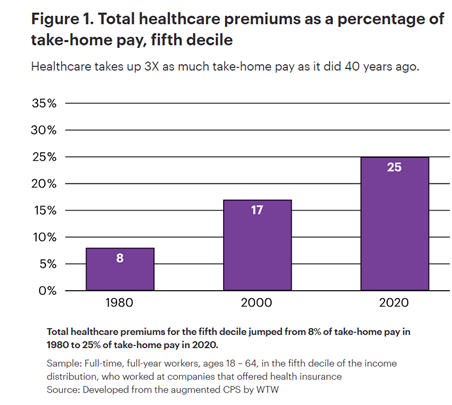

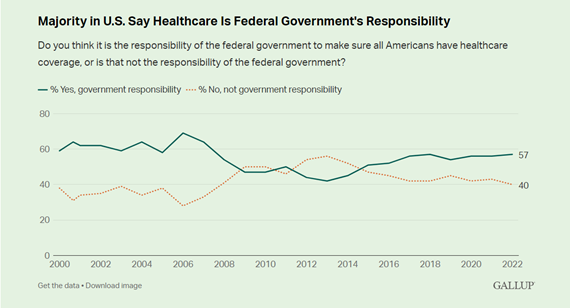

The first potential reason that is often presented is that unlike the majority of Europe, Canada, Latin America, etc., Americans do not like to be given handouts. After all, they reside in the ‘land of the free’, where barriers to success and wealth are supposedly infinitesimal. Why should you need the state to pay your healthcare bills, when if you just worked harder, you would be able to afford them yourself? This is the rhetoric of many traditional, free-market conservatives and moderates whose voices have dominated the debate on healthcare for decades. Unfortunately, this patriotic verbosity does little for the economic standpoint of most Americans, who often find themselves unable to pay their medical dues as a result of stagnant wages and rising healthcare costs. 2018 data from Bankrate concluded that less than 40% of the American population would have the necessary savings to finance a $1,000 emergency room visit without going into debt. With medical costs taking up more and more of the average American’s disposable income, it’s fairly safe to assume that the nation’s citizens are likely discontent with the current system, and hindering the traditional argument that Americans don’t need or like the idea of universal healthcare. Recent polls also reflect this, including one by Gallup in 2022 that shows almost 60% of the nation believes the government has a duty to provide healthcare.

Another common trope found among American healthcare discourse is that universal healthcare is too expensive for the average citizen. Even prominent advocates of a single-payer universal system like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren admit that tax rises are inevitable to fund such a programme without huge federal budget redistribution. So, if this change to the system is going to result in less disposable income for the average American, why would it be implemented? Well, the accuracy of this claim should not necessarily be wholeheartedly believed. In fact, the overall spend on healthcare per citizen could very well decrease with a single-payer system, despite the tax rises that would seemingly ensue.

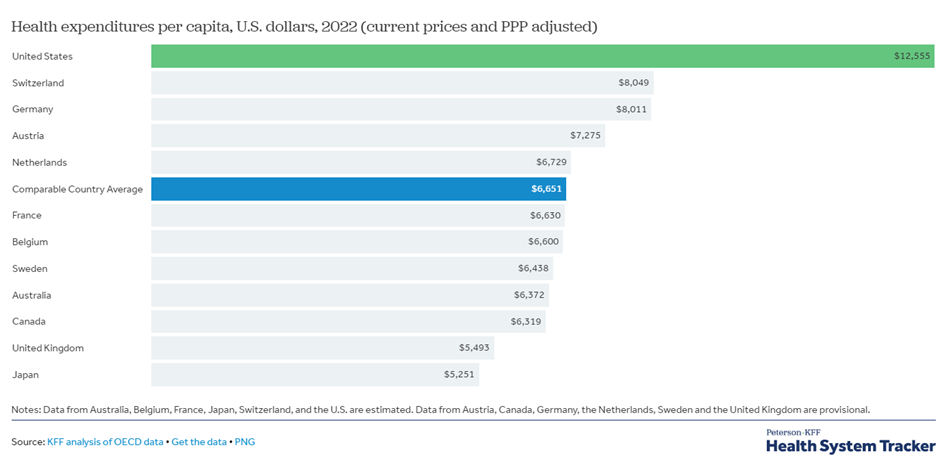

According to data analysis conducted by Peterson-KFF, the United States spends over double on healthcare per person than the United Kingdom, a nation with a well-established state-run system: the NHS. The reason for this is because of the monopsony power that comes with being a single buyer, which the government is in universal healthcare systems. With no one else to sell medical equipment, prescription drugs, etc. to apart from the government, the private pharmaceutical and medical firms are forced to lower their prices, resulting in much cheaper medical resources that can be financed by small tax raises, as opposed to spending much more individually on insurance in a privatised system. The elimination of insurance companies also contributes to the reduction in healthcare spending per capita, as the government does not provide a ‘for profit’ service the way that insurance firms do.

So, if the reason for the absence of universal healthcare in the US is not its lack of popularity with the electorate, and it isn’t its exorbitant cost to the taxpayer – what is the reason? Why isn’t it a contentious issue at the forefront of political debates come election time? Where are the politicians representing the majority opinion on it? It is within this last question in which the most likely reason for a lack of pressure for universal healthcare in the US can be found. That reason is lobbyists.

As investigated by STAT, in the year leading up to the 2020 presidential election, almost three quarters of the US Senate and two thirds of the US House of Representatives accepted money for their campaigns from a firm within the pharmaceutical industry. One Republican congressman, Richard Hudson, was the recipient of over $130,000 from the industry despite his lack of political prowess and influence over legislation. It is logical to assume that lucrative, powerful industries such as pharmaceuticals are not donating money to congressional PACs out of benevolence. It is essentially an investment, which will save the industry money in the long term despite the initial cost. The actions of senate Democrat Chris Coons illustrate the partnership between lawmakers and the private medical industry comprehensibly. In the last 5 years, Coons has been the beneficiary of nearly $500,000 from ‘Big Pharma’. In return, he has used his coveted position on the Judiciary Committee in the Senate to protect and expand patents for drug innovations, thereby hugely increasing the profitability of the industry.

This influence over US politicians in order to preserve or augment their profits extends to the universal healthcare debate, too. According to Pharmaphorum, a universal system would decrease the annual revenue of the pharmaceutical industry by around 25% – a devastating loss. So in conjunction with expanding patent rights and fighting regulation, legislators receiving their campaign finance are expected to vehemently oppose this ‘socialised’ healthcare system and vocalise deterrents to it, such as the ones discussed earlier about its unpopularity and level of expense to the taxpayer, despite these claims being easily falsified.

It is for this unfortunate reason that universal healthcare will not get the exposure it deserves on the political stage in America – with the few candidates advocating for it often not well supported by the political establishment and lobbyists. Mass organization against these few candidates often lead to their failure – most notably Bernie Sanders in both the 2016 and 2020 Democratic primaries, where Sanders claimed the Democratic National Committee obstructed his victory by blatantly favouring Clinton and Biden in ’16 and ’20 respectively. Both candidates were significantly more outspoken against universal healthcare.

So, whilst there are certainly huge obstacles obstructing the United States’ path to join the rest of the industrialised world in healthcare, they are not the conventional hurdles that are often talked about. In fact, the real hindrance is the legitimisation of said hurdles by the media and legislators, as the pharmaceutical industry continues to buy the voices of politicians to convince the American public that universal healthcare is, as Hillary Clinton said, “never ever going to happen”.