A New Right for a New Generation? Reform UK and the Collapse of Traditional Alignments

*Disclaimer: upon request of the author: “All opinions and thoughts expressed are the authors, and are not linked to any organisation or group”.*

Introduction

In the recent local elections in the United Kingdom, the long-standing dominance of the two major parties—Labour and the Conservatives—was notably disrupted by the electoral success of Reform UK. The party secured 677 of approximately 1,600 seats contested across England, predominantly in Conservative-held councils that were last voted on in 2021.

Although local elections are typically smaller in scale and often not entirely indicative of general election outcomes, the current political landscape suggests that Reform UK’s national vote share could surpass 30% in an upcoming general election. During the campaign, Reform UK adopted rhetoric closely resembling that of Donald Trump, pledging that councils and mayoralties under their control would oppose asylum seeker accommodations and dismantle equality and diversity programmes.

Nigel Farage’s discourse echoed this combative populism. In his post-election speech, he openly mocked local councils focused on climate initiatives and diversity, equity, and inclusion agendas, declaring that public officials who supported such measures or worked remotely should begin “seeking alternative careers very, very quickly.”

Farage has also sought to strengthen his international political alliances, particularly with actors in the United States. In January, he announced plans to visit the U.S. to repair and bolster his ties with Elon Musk, who has recently become an influential figure in right-wing political discourse and a close ally of Donald Trump. This move followed Musk’s controversial remarks suggesting that the leadership of Reform UK should be replaced.

Given these developments, a key question arises: How has Reform UK, a relatively new and previously marginal party, managed to disrupt a political system dominated for nearly a century by Labour and the Conservatives? To answer this, it is essential to briefly examine the party’s roots and the career of its central figure—Nigel Farage.

Nigel Farage: A Political Trajectory

Nigel Farage’s political career began in 1999 with his election to the European Parliament as a founding member of the UK Independence Party (UKIP). He rose to national prominence when he became the party’s leader in 2006. Farage quickly distinguished himself in British politics through his flamboyant and confrontational style, which has frequently drawn comparisons to Donald Trump. Known for his outspoken and provocative rhetoric, Farage garnered media attention in 2010 after launching a viral attack on then-European Council President Herman Van Rompuy. During a speech in the European Parliament, he accused Van Rompuy of having “the charisma of a damp rag” and “the appearance of a low-grade bank clerk,” just two months before the UK’s general election.

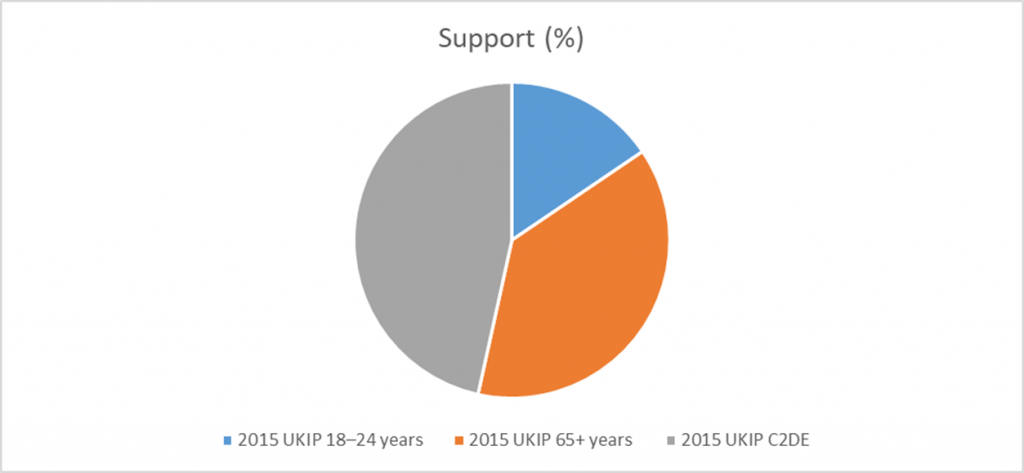

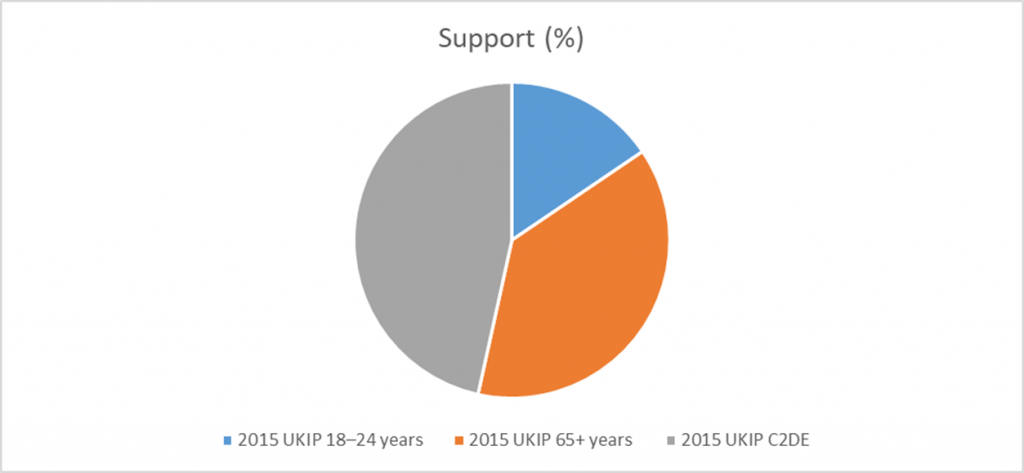

Throughout the 2010s, Farage played an increasingly pivotal role in British politics. Although UKIP held limited representation in Parliament, the party gained 24% of the national vote in the 2014 European Parliament elections, reflecting its growing influence. In the 2015 general election, UKIP captured 12% of the popular vote—a significant achievement for a party operating outside the mainstream political framework.

Farage’s most substantial political impact came through his role in championing Brexit. As one of the most visible and persistent voices in the Eurosceptic movement, Farage helped mobilize over 17 million voters in favor of leaving the European Union during the 2016 referendum. His advocacy for Brexit—rooted in his longstanding opposition to EU integration dating back to the 1990s—was instrumental in shaping public opinion. After the referendum result, he stepped down as UKIP leader, having effectively achieved his long-standing political goal of taking the UK out of the EU.

Farage returned to the political stage in 2019 under the banner of a new party—the Brexit Party—which later rebranded itself as Reform UK in 2021.

While more detailed biographical information can be found in published books and online sources, this brief overview offers the necessary context to understand Farage’s central role in the rise of Reform UK.

Socioeconomic Drivers Behind Reform UK’s Rise: Beyond Immigration

The question that arises is how Nigel Farage—often perceived as a populist entertainer rather than a conventional statesman—managed to lead Reform UK to national prominence, challenging the near century-long political dominance of the Conservative and Labour parties.

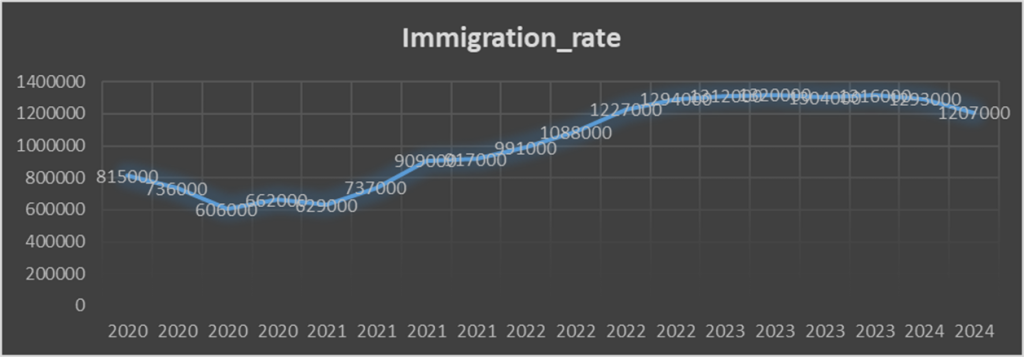

At first glance, the most immediate explanation lies in the surge of immigration to the United Kingdom in recent years, which has fueled public anxieties about national identity, security, and social cohesion. This has created fertile ground for far-right narratives, allowing parties like Reform UK to present themselves as protectors of national interests. However, is immigration alone sufficient to explain this political realignment?

Source:YouGov

To explore this question, I conducted a quantitative analysis using basic linear regression models to examine the relationship between immigration levels and support for far-right parties over time. The initial bivariate model revealed a positive but statistically insignificant correlation between immigration and far-right political support (p = 0.208), with a very low explanatory power (R² = 0.03). This suggests that immigration, in isolation, does not adequately account for variations in far-right vote share.

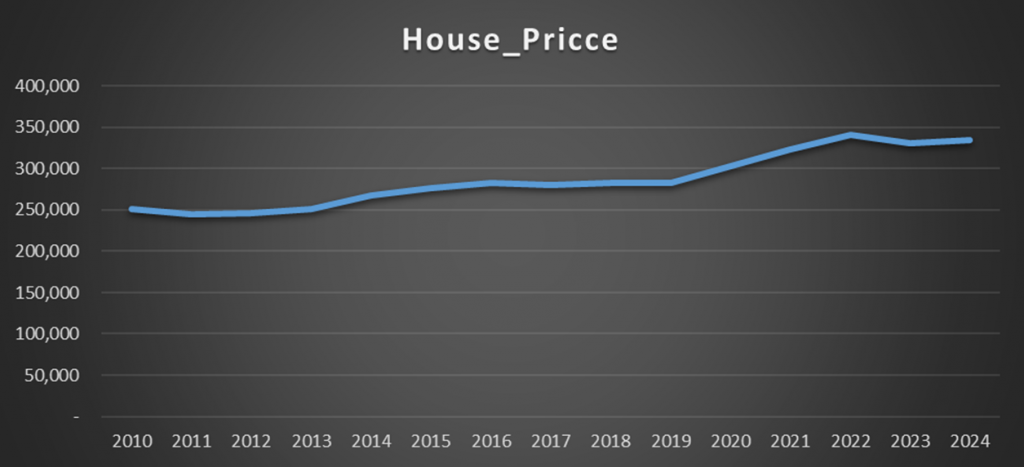

However, the results shifted significantly when housing prices were added as a second independent variable in a multivariate regression model. In this adjusted model, immigration became a statistically significant predictor (p = 0.007), and the overall model fit improved substantially (R² = 0.135). This outcome highlights the importance of including socioeconomic variables—such as housing affordability—in analyses of political behavior. Rising housing costs may act as a confounding factor, masking the true influence of immigration or exacerbating public frustration, which in turn can lead to increased support for populist parties. Visual representations, including scatterplots and regression lines, further reinforced how the inclusion of housing prices clarified the relationship between immigration and political extremism.

These findings suggest that Farage’s success is not driven solely by anti-immigration sentiment but also amplified by broader indicators of economic instability. In fact, financial hardship and declining living standards appear to be more influential. Recent data indicate that lower-income voters increasingly favor Reform UK over the Labour Party—a surprising trend given that Labour traditionally champions income equality and social welfare. The erosion of trust in Labour among economically vulnerable groups may stem, in part, from Farage’s cultivated image as an ordinary citizen. Unlike the often technocratic figures of Labour and the Conservatives, Farage presents himself as “a man in the pub”—casual, relatable, and skeptical of political correctness. This image enables him to connect with voters who feel alienated from mainstream politics and are seeking authenticity and simplicity in leadership.

The socioeconomic pressures faced by younger generations further contextualize Reform UK’s rise. House prices in the UK have surged consistently over the past decades, placing home ownership increasingly out of reach for many young adults. A report by The Guardian reveals that significant numbers of young people, particularly men, now live with their parents well into adulthood. The number of non-dependent adult children living at home has risen by nearly 15%, reaching approximately 4.9 million, with an average age of 24. These figures suggest a prolonged adolescence and delayed economic independence, with broader implications for political engagement and identity formation.

Source:YouGov

In 1997, over half of 21-year-olds had already left the parental home, and the typical living arrangement for 18- to 34-year-olds was living as part of a couple with children. By the 2021 census, however, the most common scenario for individuals in their early twenties was living with their parents. Notably, this trend affects not only the youngest adults: approximately 30% of those aged 25 to 29 still live at home, and the proportion of 30- to 34-year-olds in the same situation has increased from 8.6% in 2011 to 11.6% in 2021.

This generational economic stagnation—manifested in unaffordable housing, precarious employment, and rising living costs—has contributed significantly to the appeal of Reform UK, particularly among younger and financially insecure voters. Farage’s messaging, combined with these structural factors, has enabled the party to position itself as a voice for the economically disenfranchised.

Generational Realignment: Youth, Masculinity, and the Populist Appeal of Reform UK

Unsurprisingly, Nigel Farage and Reform UK have gained significant traction among younger demographics, particularly within lower-income groups. Recent data indicates a marked increase in support from young voters who feel disillusioned with mainstream political parties and increasingly see Reform UK as a viable alternative.

In the 2015 general election, support for Reform UK (then operating under the Brexit Party label) among the 18–24 age group stood at just 9%, according to The Times. However, polling from YouGov suggests that by early 2024, this figure had more than doubled, with support among voters under 24 peaking at 19%.

Source: The Times

Source: The Times

Another article in The Guardian highlights an especially notable trend among young men, who appear significantly more likely than young women to support Reform UK. While young women have shown greater affinity toward progressive parties like the Greens, young men are reportedly twice as likely to back Reform in the upcoming general election. Although this demographic is relatively small and difficult to capture with complete precision, the sharp uptick in their support reflects a broader international shift toward right-wing populism among Generation Z.

This generational realignment is largely driven by growing frustration with mainstream political institutions. Many young people perceive the two dominant parties—Labour and the Conservatives—as having failed to deliver substantive change, particularly on pressing issues like housing affordability, income insecurity, and public services. Historically, such anti-establishment sentiment among youth was more likely to manifest in support for the radical left. However, recent political behavior suggests that this frustration is now being redirected toward populist right-wing movements like Reform UK.

Farage’s appeal to this demographic is partly rooted in cultural symbolism. He positions himself as a champion of British identity and traditional values, presenting a stark contrast to what many young men see as an overly progressive or “woke” political culture. According to interviews conducted by The Guardian, some young male voters feel that “woke culture” and modern feminism have marginalized traditional masculinity and suppressed what they view as legitimate expressions of male identity. These cultural grievances, alongside economic pressures, have made Farage’s rhetoric resonate deeply—particularly his emphasis on nationalism, personal responsibility, and anti-elitism.

Reform UK’s messaging strategy often relies on simplistic but effective narratives: “Do you have financial problems? Blame migrants. Can’t afford a house? Blame migrants.” While these messages lack policy depth, they offer emotionally compelling explanations for complex issues, which can be especially persuasive among economically insecure youth.

Labour, once the natural home of working-class and low-income voters, has increasingly repositioned itself around middle- and upper-middle-class constituencies, often focusing on post-materialist concerns such as climate change, gender identity, and inclusivity. As a result, the party has struggled to address the immediate, material concerns of many young people—particularly young men—who feel left behind by cultural and economic transformation. This mirrors a similar phenomenon observed in the United States during the 2016 and 2020 elections, where Donald Trump’s appeal to “ordinary working people” outpaced traditional Democratic messaging among key blue-collar voter groups.

Conclusion

To sum up, Farage’s success in the local elections cannot be attributed solely to his stance on migration. A key factor has been his ability to connect with young people facing economic hardship and a sense of social exclusion—groups that feel increasingly neglected by the political mainstream. Labour has so far failed to respond effectively to this growing gap in representation.

However, this failure is not unique to the UK. A similar trend occurred in the United States, where Donald Trump capitalized on the same vacuum. Labour must move beyond its traditional discourse and prioritize tangible solutions to housing inflation, youth unemployment, and economic insecurity. While the Conservatives suffered losses in recent elections due to fiscal mismanagement, Labour benefited from this vacuum—but Reform UK now appears poised to do the same.

Ultimately, the party’s rise reflects the intersection of economic, cultural, and political grievances. Immigration may remain a focal point of its messaging, but rising living costs, financial instability, and a broader sense of cultural displacement—especially among young, working-class men—are driving deeper support.

Farage’s populist persona, combined with growing frustration toward both Labour and the Conservatives, has allowed Reform UK to occupy a political space that feels more authentic to many disaffected voters. If mainstream parties aim to halt this momentum, they must re-establish trust through concrete policies and a renewed political narrative that speaks directly to the everyday realities of those they have overlooked.

Ibrahim Melih Polat

MSc University of Exeter